- Home

- Terry Pratchett

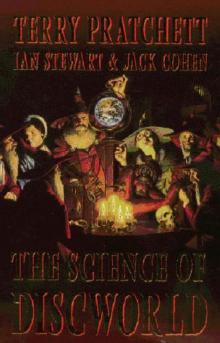

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition Read online

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Book

Also by Terry Pratchett, Ian Stewart & Jack Cohen

Title Page

The Story Starts Here

1. SPLITING THE THAUM

2. SQUASH COURT SCIENCE

3. I KNOW MY WIZARDS

4. SCIENCE AND MAGIC

5. THE ROUNDWORLD PROJECT

6. BEGINNINGS AND BECOMINGS

7. BEYOND THE FIFTH ELEMENT

8. WE ARE STARDUST (OR, AT LEAST WE WENT TO WOODSTOCK)

9. EAT HOT NAPHTHA, EVIL DOG!

10. THE SHAPE OF THINGS

11. NEVER TRUST A CURVED UNIVERSE

12. WHERE DO RULES COME FROM?

13. NO IT CAN’T DO THAT

14. DISC WORLDS

15. THE DAWN OF DAWN

16. EARTH AND FIRE

17. SUIT OF SPELLS

18. ARE AND WATER

19. THERE IS A TIDE

20. A GIANT LEAP FOR MOONKIND

21. THE LIGHT YOU SEE THE DARK BY

22. THINGS THAT AREN’T

23. NO POSSIBILITY OF LIFE

24. DESPITE WHICH

25. UNNATURAL SELECTION

26. THE DESCENT OF DARWIN

27. WE NEED MORE BLOBS

28. THE ICEBERG COMETH

29. GOING FOR A PADDLE

30. UNIVERSALS AND PAROCHIALS

31. GREAT LEAP SIDEWAYS

32. DON’T LOOK UP

33. THE FUTURE IS NEWT

34. NINE TIMES OUT OF TEN

35. STIL BLOODY LIZARDS

36. RUNNING FROM DINOSAURS

37. I SAID, DON’T LOOK UP

38. THE DEATH OF DINOSAURS

39. BACKSLIDERS

40. MAMMALS ON THE MAKE

41. DON’T PLAY GOD

42. ANTHILL INSIDE

43. OOK: A SPACE ODYSSEY

44. EXTEL OUTSIDE

45. THE BLEAT GOES ON

46. WAYS TO LEAVE YOUR PLANET

47. YOU NEED CHELONIUM

48. EDEN AND CAMELOT

49. AS ABOVE, SO BELOW

Index

Copyright

About the Book

When a thaumic experiment goes adrift, the wizards of Unseen University find that they’ve accidentally created a new universe. Within it is a planet that they name Roundworld, an extraordinary place where neither magic nor common sense seems to stand a chance against logic.

The universe, of course, is our own. And Roundworld is Earth. As the wizards watch their accidental creation grow, we follow the story of our universe from the primal singularity of the Big Bang to the evolution of life on Earth and beyond.

This original Terry Pratchett story, inverwoven with chapters from Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart, offers a wonderful wizard’s-eye view of our universe. Once you’ve seen the world from a Discworld perspective, it will never seem the same again...

BY THE SAME AUTHORS:

TERRY PRATCHETT

THE CARPET PEOPLE • THE DARK SIDE OF THE SUN • STRATA

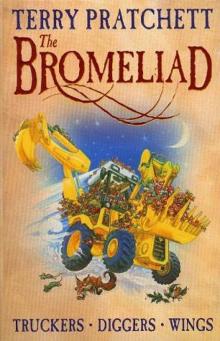

TRUCKERS • DIGGERS • WINGS • ONLY YOU CAN SAVE MANKIND •

JOHNNY AND THE DEAD • JOHNNY AND THE BOMB

THE UNADULTERATED CAT (with Gray Jolliffe) • GOOD OMENS (with Neil Gaiman) •THE PRATCHETT PORTFOLIO (with Paul Kidby)

THE DISCWORLD ® SERIES:

THE COLOUR OF MAGIC • THE LIGHT FANTASTIC • EQUAL RITES •

MORT • SOURCERY • WYRD SISTERS • PYRAMIDS • GUARDS! GUARDS!

ERIC (with Josh Kirby) • MOVING PICTURES • REAPER MAN

WITCHES ABROAD • SMALL GODS • LORDS AND LADIES • MEN AT ARMS

SOUL MUSIC • INTERESTING TIMES • MASKERADE • FEET OF CLAY

HOGFATHER • JINGO • THE LAST CONTINENT • CARPE JUGULUM

THE FIFTH ELEPHANT • THE TRUTH • THIEF OF TIME

THE AMAZING MAURICE AND HIS EDUCATED RODENTS •

THE SCIENCE OF DISCWORLD II (with Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen)

THE COLOUR OF MAGIC (graphic novel)

THE LIGHT FANTASTIC (graphic novel)

MORT: A DISCWORLD BIG COMIC (with Graham Higgins)

SOUL MUSIC: The illustrated screenplay

WYRD SISTERS: The illustrated screenplay

MORT – THE PLAY (adapted by Stephen Briggs)

WYRD SISTERS (adapted by Stephen Briggs)

GUARDS! GUARDS! (adapted by Stephen Briggs)

MEN AT ARMS (adapted by Stephen Briggs)

THE DISCWORLD COMPANION (with Stephen Briggs)

THE STREETS OF ANKH-MORPORK (with Stephen Briggs)

THE DISCWORLD MAPP (with Stephen Briggs)

A TOURIST GUIDE TO LANCRE a Discworld Mapp (with Stephen Briggs and Paul Kidby) • DEATH’S DOMAIN (with Paul Kidby) • NANNY OGG’S COOKBOOK

IAN STEWART

CONCEPTS OF MODERN MATHEMATICS • GAME, SET, AND MATH

THE PROBLEMS OF MATHEMATICS • DOES GOD PLAY DICE?

ANOTHER FINE MATH YOU’VE GOT ME INTO • FEARFUL SYMMETRY

NATURE’S NUMBERS • FROM HERE TO INFINITY • THE MAGICAL MAZE

LIFE’S OTHER SECRET • FLATTERLAND • WHAT SHAPE IS A SNOWFLAKE?

THE ANNOTATED FLATLAND

JACK COHEN

LIVING EMBRYOS • REPRODUCTION • PARENTS MAKING PARENTS

SPERMS, ANTIBODIES AND INFERTILITY • THE PRIVILEGED APE

STOP WORKING AND START THINKING (with Graham Medley)

IAN STEWART AND JACK COHEN

THE COLLAPSE OF CHAOS • FIGMENTS OF REALITY

WHEELERS • EVOLVING THE ALIEN

‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’

ARTHUR C. CLARKE

_____

‘Any technology distinguishable from magic is insufficiently advanced’

GREGORY BENFORD

_____

‘The reason why truth is so much stranger than fiction is that there is no requirement for it to be consistent.’

MARK TWAIN

_____

‘There are no turtles anywhere’

PONDER STIBBONS

THE STORY STARTS HERE …

ONCE UPON A time, there was Discworld. There still is an adequate supply.

Discworld is the flat world, carried through space on the back of a giant turtle, which has been the source of – so far – twenty-seven novels, four maps, an encylopaedia, two animated series, t-shirts, scarves, models, badges, beer, embroidery, pens, posters, and probably, by the time this is published, talcum power and body splash (if not, it can only be a matter of time).

It has, in short, become immensely popular.

And Discworld runs on magic.

Roundworld – our home planet, and by extension the universe in which it sits – runs on rules. In fact, it simply runs. But we have watched the running, and those observations and the ensuing deductions are the very basis of science.

Magicians and scientists are, on the face of it, poles apart. Certainly, a group of people who often dress strangely, live in a world of their own, speak a specialized language and frequently make statements that appear to be in flagrant breach of common sense have nothing in common with a group of people who often dress strangely, speak a specialized language, live in … er …

Perhaps we should try this another way. Is there a connection between magic and science? Can the magic of Discworld, with its eccentric wizards, down-to-Earth witches, obstinate trolls, fire-breathing dragons, talking dogs, and personified DEATH, shed any useful light on hard, rational, solid, Earthly science?

We think so.

We’ll explain why in a moment, but first, let’s make it clear what The Science of D

iscworld is not. There have been several media tie-in The Science of … books, such as The Science of the X-Files and The Physics of Star Trek. They tell you about areas of today’s science that may one day lead to the events or devices that the fiction depicts. Did aliens crash-land at Roswell? Could an anti-matter warp drive ever be invented? Could we ever have the ultra long-life batteries that Scully and Mulder must be using in those torches of theirs?

We could have taken that approach. We could, for example, have pointed out that Darwin’s theory of evolution explains how lower lifeforms can evolve into higher ones, which in turn makes it entirely reasonable that a human should evolve into an orangutan (while remaining a librarian, since there is no higher life form than a librarian). We could have speculated on which DNA sequence might reliably incorporate asbestos linings into the insides of dragons. We might even have attempted to explain how you could get a turtle ten thousand miles long.

We decided not to do these things, for a good reason … um, two reasons.

The first is that it would be … er … dumb.

And this because of the second reason. Discworld does not run on scientific lines. Why pretend that it might? Dragons don’t breathe fire because they’ve got asbestos lungs – they breathe fire because everyone knows that’s what dragons do.

What runs Discworld is deeper than mere magic and more powerful than pallid science. It is narrative imperative, the power of story. It plays a role similar to that substance known as phlogiston, once believed to be that principle or substance within inflammable things that enabled them to burn. In the Discworld universe, then, there is narrativium. It is part of the spin of every atom, the drift of every cloud. It is what causes them to be what they are and continue to exist and take part in the ongoing story of the world.

On Roundworld, things happen because the things want to happen.1 What people want does not greatly figure in the scheme of things, and the universe isn’t there to tell a story.

With magic, you can turn a frog into a prince. With science, you can turn a frog into a Ph.D and you still have the frog you started with.

That’s the conventional view of Roundworld science. It misses a lot of what actually makes science tick. Science doesn’t just exist in the abstract. You could grind the universe into its component particles without finding a single trace of Science. Science is a structure created and maintained by people. And people choose what interests them, and what they consider to be significant and, quite often, they have thought narratively.

Narrativium is powerful stuff. We have always had a drive to paint stories on to the Universe. When humans first looked at the stars, which are great flaming suns an unimaginable distance away, they saw in amongst them giant bulls, dragons, and local heroes.

This human trait doesn’t affect what the rules say – not much, anyway – but it does determine which rules we are willing to contemplate in the first place. Moreover, the rules of the universe have to be able to produce everything that we humans observe, which introduces a kind of narrative imperative into science too. Humans think in stories2. Classically, at least, science itself has been the discovery of ‘stories’ – think of all those books that had titles like The Story of Mankind, The Descent of Man, and, if it comes to that, A Brief History of Time.

Over and above the stories of science, though, Discworld can play an even more important role: What if? We can use Discworld for thought experiments about what science might have looked like if the universe had been different, or if the history of science had followed a different route. We can look at science from the outside.

To a scientist, a thought experiment is an argument that you can run through in your head, after which you understand what’s going on so well that there’s no need to do a real experiment, which is of course a great saving in time and money and prevents you from getting embarrassingly inconvenient results. Discworld takes a more practical view – there, a thought experiment is one that you can’t do and which wouldn’t work if you could. But the kind of thought experiment we have in mind is one that scientists carry out all the time, usually without realizing it; and you don’t need to do it, because the whole point is that it wouldn’t work. Many of the most important questions in science, and about our understanding of it, are not about how the universe actually is. They are about what would happen if the universe were different.

Someone asks ‘why do zebras form herds?’ You could answer this by an analysis of zebra sociology, psychology, and so on … or you could ask a question of a very different kind: ‘What would happen if they didn’t?’ One fairly obvious answer to that is ‘They’d be much more likely to get eaten by lions.’ This immediately suggests that zebras form herds for self-protection – and now we’ve got some insight into what zebras actually do by contemplating, for a moment, the possibility that they might have done something else.

Another, more serious example is the question ‘Is the solar system stable?’, which means ‘Could it change dramatically as a result of some tiny disturbance?’ In 1887 King Oscar II of Sweden offered a prize of 2,500 crowns for the answer. It took about a century for the world’s mathematicians to come up with a definite answer: ‘Maybe’. (It was a good answer, but they didn’t get paid. The prize had already been awarded to someone who didn’t get the answer and whose prizewinning article had a big mistake right at the most interesting part. But when he put it right, at his own expense, he invented Chaos Theory and paved the way for the ‘maybe’. Sometimes, the best answer is a more interesting question.) The point here is that stability is not about what a system is actually doing: it is about how the system would change if you disturbed it. Stability, by definition, deals with ‘what if?’.

Because a lot of science is really about this non-existent world of thought experiments, our understanding of science must concern itself with worlds of the imagination as well as with worlds of reality. Imagination, rather than mere intelligence, is the truly human quality. And what better world of the imagination to start from than Discworld? Discworld is a consistent, well-developed universe with its own kinds of rules, and convincingly real people live on it despite the substantial differences between their universe’s rules and ours. Many of them also have a thoroughgoing grounding in ‘common sense’, one of science’s natural enemies.

Appearing regularly within the Discworld canon are the buildings and faculty of Unseen University, the Discworld’s premier college of magic. The wizards3 are a lively bunch, always ready to open any door that has ‘This door to be kept shut’ written on it or pick up anything that has just started to fizz. It seemed to us that they could be useful …

Clearly, as the wizards of Unseen University believe, this world is a parody of the Discworld one. If we, or they, compare Discworld’s magic to Roundworld science, the more similarities and parallels we find. And when we didn’t discover parallels, we found that the differences were very revealing. Science takes on a new character when you stop asking questions like ‘What does newt DNA look like?’ and instead ask ‘I wonder how the wizards would react to this way of thinking about newts?’

There is no science as such on Discworld. So we have put some there. By magical means, the wizards on Discworld are led to create their own brand of science – some kind of ‘pocket universe’ in which magic no longer works, but rules do. Then, as the wizards learn to understand how the rules make interesting things happen – rocks, bacteria, civilizations – we watch them watching … well, us. It’s a sort of recursive thought experiment, or a Russian doll wherein the smaller dolls are opened up to find the largest doll inside.

And then we found that … ah, but that is another story.

TP, IS, & JC, DECEMBER 1998

PS We have, we are afraid, mentioned in the ensuing pages Schrödinger’s Cat, the Twins Paradox, and that bit about shining a torch ahead of a spaceship travelling at the speed of light. This is because, under the rules of the Guild of Science Writers, they have to be included. We have, however, tried

to keep them short.

We’ve managed to be very, very brief about the Trousers of Time, as well.

PPS Sometimes scientists change their minds. New developments cause a rethink. If this bothers you, consider how much damage is being done to the world by people for whom new developments do not cause a rethink.

This second edition has been changed to reflect three years of scientific progress … forwards or backwards. (You will find both.) And we’ve added two completely new chapters: one on the life of dinosaurs, because the existing chapter on the death of dinosaurs seemed a bit depressing; and one on cosmic disasters, because in many ways the universe is depressing.

The Discworld story has proved more robust than the science. As should be expected. Discworld makes so much more sense than Roundworld does.

TP, IS, & JC, JANUARY 2002

1 In a manner of speaking. They happen because things obey the rules of the universe. A rock has no detectable opinion about gravity.

2 It took three years for this sentence to sink in. When it did, we wrote The Science of Discworld II: The Globe.

3 Like the denizens of any Roundworld university, they have unlimited time for research, unlimited funds and no worries about tenure. They are also by turns erratic, inventively malicious, resistant to new ideas until they’ve become old ideas, highly creative at odd moments and perpetually argumentative – in this respect they bear no relation to their Roundworld counterparts at all.

ONE

SPLITTING THE THAUM

SOME QUESTIONS SHOULD not be asked. However, someone always does.

‘How does it work?’ said Archchancellor Mustrum Ridcully, the Master of Unseen University.

This was the kind of question that Ponder Stibbons hated almost as much as ‘How much will it cost?’ They were two of the hardest questions a researcher ever had to face. As the university’s de facto head of magical development, he especially tried to avoid questions of finance at all costs.

‘In quite a complex way,’ he ventured at last.

‘Ah.’

‘What I’d like to know,’ said the Senior Wrangler, ‘is when we’re going to get the squash court back.’

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II