- Home

- Terry Pratchett

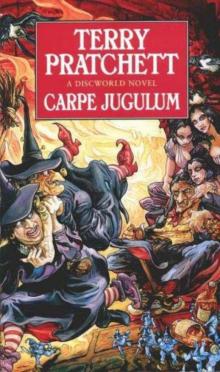

Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Read online

Terry Pratchett

CARPE JUGULUM

A Novel of Discworld®

Contents

Begin Reading

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Terry Pratchett

Copyright

About the Publisher

Begin Reading

Through the shredded black clouds a fire moved like a dying star, falling back to earth—

—the earth, that is, of the Discworld—

—but unlike any star had ever done before, it sometimes managed to steer its fall, sometimes rising, sometimes twisting, but inevitably heading down.

Snow glowed briefly on the mountain slopes when it crackled overhead.

Under it, the land itself started to fall away. The fire was reflected off walls of blue ice as the light dropped into the beginnings of a canyon and thundered now through its twists and turns.

The light snapped off. Something still glided down the moonlit ribbon between the rocks.

It shot out of the canyon at the top of a cliff, where meltwater from a glacier plunged down into a distant pool.

Against all reason there was a valley here, or a network of valleys, clinging to the edge of the mountains before the long fall to the plains. A small lake gleamed in the warmer air. There were forests. There were tiny fields, like a patchwork quilt thrown across the rocks.

The wind had died. The air was warmer.

The shadow began to circle.

Far below, unheeded and unheeding, something else was entering this little handful of valleys. It was hard to see exactly what it was; furze rippled, heather rustled, as if a very large army made of very small creatures was moving with one purpose.

The shadow reached a flat rock that offered a magnificent view of the fields and wood below, and there the army came out from among the roots. It was made up of very small blue men, some wearing pointy blue caps but most of them with their red hair uncovered. They carried swords. None of them was more than six inches high.

They lined up and looked down into the new place and then, weapons waving, raised a battle cry. It would have been more impressive if they’d all agreed on one before, but as it was it sounded as though every single small warrior had a battle cry of his very own and would fight anyone who tried to take it away from him.

“Nac mac Feegle!”

“Ach, stickit yer trakkans!”

“Gie you sich a kickin’!”

“Bigjobs!”

“Dere c’n onlie be whin t’ousand!”

“Nac mac Feegle wha hae!”

“Wha hae yersel, ya boggin!”

The little cup of valleys, glowing in the last shreds of evening sunlight, was the kingdom of Lancre. From its highest points, people said, you could see all the way to the rim of the world.

It was also said, although not by the people who lived in Lancre, that below the rim, where the seas thundered continuously over the edge, their home went through space on the back of four huge elephants that in turn stood on the shell of a turtle that was as big as the world.

The people of Lancre had heard of this. They thought it sounded about right. The world was obviously flat, although in Lancre itself the only truly flat places were tables and the top of some people’s heads, and certainly turtles could shift a fair load. Elephants, by all accounts, were pretty strong too. There didn’t seem any major gaps in the thesis, so Lancrastrians left it at that.

It wasn’t that they didn’t take an interest in the world around them. On the contrary, they had a deep, personal and passionate involvement in it, but instead of asking “why are we here?” they asked “is it going to rain before the harvest?”

A philosopher might have deplored this lack of mental ambition, but only if he was really certain about where his next meal was coming from.

In fact Lancre’s position and climate bred a hardheaded and straightforward people who often excelled in the world down below. It had supplied the plains with many of their greatest wizards and witches and, once again, the philosopher might have marveled that such a four-square people could give the world so many successful magical practitioners, being quite unaware that only those with their feet on rock can build castles in the air.

And so the sons and daughters of Lancre went off into the world, carved out careers, climbed the various ladders of achievement, and always remembered to send money home.

Apart from noting the return addresses on the envelope, those who stayed didn’t think much about the world outside.

The world outside thought about them, though.

The big flat-topped rock was deserted now, but on the moor below, the heather trembled in a V-shape heading toward the lowlands.

“Gin’s a haddie!”

“Nac mac Feegle!”

There are many kinds of vampires. Indeed, it is said that there are as many kinds of vampires as there are types of disease.* And they’re not just human (if vampires are human). All along the Ramtops may be found the belief that any apparently innocent tool, be it hammer or saw, will seek blood if left unused for more than three years. In Ghat they believe in vampire watermelons, although folklore is silent about what they believe about vampire watermelons. Possibly they suck back.

Two things have traditionally puzzled vampire researchers. One is: why do vampires have so much power? Vampires’re so easy to kill, they point out. There are dozens of ways to dispatch them, quite apart from the stake through the heart, which also works on normal people so if you have any stakes left over you don’t have to waste them. Classically, they spent the day in some coffin somewhere, with no guard other than an elderly hunchback who doesn’t look all that spry and should succumb to quite a small mob. Yet just one can keep a whole community in a state of sullen obedience…

The other puzzle is: why are vampires always so stupid? As if wearing evening dress all day wasn’t an undead giveaway, why do they choose to live in old castles which offer so much in the way of ways to defeat a vampire, like easily torn curtains and wall decorations that can readily be twisted into a religious symbol? Do they really think that spelling their name backward fools anyone?

A coach rattled across the moorlands, many miles away from Lancre. From the way it bounced over the ruts, it was traveling light. But darkness came with it.

The horses were black, and so was the coach, except for the coat of arms on the doors. Each horse had a black plume between its ears; there was a black plume at each corner of the coach as well. Perhaps these caused the coach’s strange effect of traveling shadow. It seemed to be dragging the night behind it.

On the top of the moor, where a few trees grew out of the rubble of a ruined building, it creaked to a halt.

The horses stood still, occasionally stamping a hoof or tossing their heads. The coachman sat hunched over the reins, waiting.

Four figures flew just above the clouds, in the silvery moonlight. By the sound of their conversation someone was annoyed, although the sharp unpleasant tone to the voice suggested that a better word might be “vexed.”

“You let it get away!” This voice had a whine to it, the voice of a chronic complainer.

“It was wounded, Lacci.” This voice sounded conciliatory, parental, but with just a hint of a repressed desire to give the first voice a thick ear.

“I really hate those things. They’re so…soppy!”

“Yes, dear. A symbol of a credulous past.”

“If I could burn like that I wouldn’t skulk around just looking pretty. Why do they do it?”

“It must have been of use to them at one time, I suppose.”

“Then they’re…what did you call them?”

“An evolutionary cul-de-sac, Lacci. A marooned survivor on the seas of progress.”<

br />

“Then I’m doing them a favor by killing them?”

“Yes, that is a point. Now, shall—”

“After all, chickens don’t burn,” said the voice called Lacci. “Not easily, anyway.”

“We heard you experiment. Killing them first might have been a good idea.” This was a third voice—young, male, and also somewhat weary with the female. It had “older brother” harmonics on every syllable.

“What’s the point in that?”

“Well, dear, it would have been quieter.”

“Listen to your father, dear.” And this, the fourth voice, could only be a mother’s voice. It’d love the other voices whatever they did.

“You’re so unfair!”

“We did let you drop rocks on the pixies, dear. Life can’t be all fun.”

The coachman stirred as the voices descended through the clouds. And then four figures were standing a little way off. The coachman clambered down and, with difficulty, opened the coach door as they approached.

“Most of the wretched things got away, though,” said Mother.

“Never mind, my dear,” said Father.

“I really hate them. Are they a dead end too?” said Daughter.

“Not quite dead enough as yet, despite your valiant efforts. Igor! On to Lancre.”

The coachman turned.

“Yeth, marthter.”

“Oh, for the last time, man…is that any way to talk?”

“It’th the only way I know, marthter,” said Igor.

“And I told you to take the plumes off the coach, you idiot.”

The coachman shifted uneasily.

“Gotta hath black plumeth, marthter. It’th tradithional.”

“Remove them at once,” Mother commanded. “What will people think?”

“Yeth, mithtreth.”

The one addressed as Igor slammed the door and lurched back around to the horse. He removed the plumes reverentially and placed them under his seat.

Inside the coach the vexed voice said, “Is Igor an evolutionary dead end too, Father?”

“We can but hope, dear.”

“Thod,” said Igor to himself, as he picked up the reins.

The wording began:

YOU ARE CORDIALLY INVITED…

…and was in that posh runny writing that was hard to read but ever so official.

Nanny Ogg grinned and tucked the card back on the mantelpiece. She liked the idea of “cordially.” It had a rich, a thick and above all an alcoholic sound.

She was ironing her best petticoat. That is to say, she was sitting in her chair by the fire while one of her daughters-in-law, whose name she couldn’t remember just at this moment, was doing the actual work. Nanny was helping by pointing out the bits she’d missed.

It was a damn good invite, she thought. Especially the gold edging, which was as thick as syrup. Probably not real gold, but impressively glittery all the same.

“There’s a bit there that could do with goin’ over again, gel,” she said, topping up her beer.

“Yes, Nanny.”

Another daughter-in-law, whose name she’d certainly be able to recall after a few seconds’ thought, was buffing up Nanny’s red boots. A third was very carefully dabbing the lint off Nanny’s best pointed hat, on its stand.

Nanny got up again and wandered over and opened the back door. There was little light left in the sky now, and a few rags of cloud were scudding over the early stars. She sniffed the air. Winter hung on late up here in the mountains, but there was definitely a taste of spring on the wind.

A good time, she thought. Best time, really. Oh, she knew that the year started on Hogswatchnight, when the cold tide turned, but the new year started now, with green shoots boring upward through the last of the snow. Change was in the air, she could feel it in her bones.

Of course, her friend Granny Weatherwax always said you couldn’t trust bones, but Granny Weatherwax said a lot of things like that all the time.

Nanny Ogg closed the door. In the trees at the end of her garden, leafless and scratchy against the sky, something rustled its wings and chattered as a veil of dark crossed the world.

In her own cottage a few miles away the witch Agnes Nitt was in two minds about her new pointy hat. Agnes was generally in two minds about anything.

As she tucked in her hair and observed herself critically in the mirror she sang a song. She sang in harmony. Not, of course, with her reflection in the glass, because that kind of heroine will sooner or later end up singing a duet with Mr. Bluebird and other forest creatures and then there’s nothing for it but a flamethrower.

She simply sang in harmony with herself. Unless she concentrated it was happening more and more these days. Perdita had rather a reedy voice, but she insisted on joining in.

Those who are inclined to casual cruelty say that inside a fat girl is a thin girl and a lot of chocolate. Agnes’s thin girl was Perdita.

She wasn’t sure how she’d acquired the invisible passenger. Her mother had told her that when she was small she’d been in the habit of blaming accidents and mysteries, such as the disappearance of a bowl of cream or the breaking of a prized jug, on “the other little girl.”

Only now did she realize that indulging this sort of thing wasn’t a good idea when, despite yourself, you’ve got a bit of natural witchcraft in your blood. The imaginary friend had simply grown up and had never gone away and had turned out to be a pain.

Agnes disliked Perdita, who was vain, selfish and vicious, and Perdita hated going around inside Agnes, whom she regarded as a fat, pathetic, weak-willed blob that people would walk all over were she not so steep.

Agnes told herself she’d simply invented the name Perdita as some convenient label for all those thoughts and desires she knew she shouldn’t have, as a name for that troublesome little commentator that lives on everyone’s shoulder and sneers. But sometimes she thought Perdita had created Agnes for something to pummel.

Agnes tended to obey rules. Perdita didn’t. Perdita thought that not obeying rules was somehow cool. Agnes though that rules like “Don’t fall into this huge pit of spikes” were there for a purpose. Perdita thought, to take an example at random, that things like table manners were a stupid and repressive idea. Agnes, on the other hand, was against being hit by flying bits of other people’s cabbage.

Perdita thought a witch’s hat was a powerful symbol of authority. Agnes thought that a dumpy girl should not wear a tall hat, especially with black. It made her look as though someone had dropped a licorice-flavored ice-cream cone.

The trouble was that although Agnes was right, so was Perdita. The pointy hat carried a lot of weight in the Ramtops. People talked to the hat, not to the person wearing it. When people were in serious trouble they went to a witch.*

You had to wear black, too. Perdita liked black. Perdita thought black was cool. Agnes thought that black wasn’t a good color for the circumferentially challenged…oh, and that “cool” was a dumb word only used by people whose brains wouldn’t fill a spoon.

Magrat Garlick hadn’t worn black and had probably never in her life said “cool” except when commenting on the temperature.

Agnes stopped examining her pointiness in the mirror and looked around the cottage that had been Magrat’s and was now hers, and sighed. Her gaze took in the expensive, gold-edged card on the mantelpiece.

Well, Magrat had certainly retired now, and had gone off to be Queen and if there was ever any doubt about that then there could be no doubt today. Agnes was puzzled at the way Nanny Ogg and Granny Weatherwax still talked about her, though. They were proud (more or less) that she’d married the King, and agreed that it was the right kind of life for her, but while they never actually articulated the thought it hung in the air over their heads in flashing mental colors: Magrat had settled for second prize.

Agnes had almost burst out laughing when she first realized this, but you wouldn’t be able to argue with them. They wouldn’t even see that there could b

e an argument.

Granny Weatherwax lived in a cottage with a thatch so old there was quite a sprightly young tree growing in it, and got up and went to bed alone, and washed in the rain barrel. And Nanny Ogg was the most local person Agnes had ever met. She’d gone off to foreign parts, yes, but she always carried Lancre with her, like a sort of invisible hat. But they took it for granted that they were top of every tree, and the rest of the world was there for them to tinker with.

Perdita thought that being a queen was just about the best thing you could be.

Agnes though the best thing you could be was far away from Lancre, and good second best would be to be alone in your own head.

She adjusted the hat as best she could and left the cottage.

Witches never locked their doors. They never needed to.

As she stepped out into the moonlight, two magpies landed on the thatch.

The current activities of the witch Granny Weatherwax would have puzzled a hidden observer.

She peered at the flagstones just inside her back door and lifted the old rag rug in front of it with her toe.

Then she walked to the front door, which was never used, and did the same thing there. She also examined the cracks around the edges of the doors.

She went outside. There had been a sharp frost during the night, a spiteful little trick by the dying winter, and the drifts of leaves that still hung on in the shadows were crisp. In the harsh air she poked around in the flowerpots and bushes by the front door.

Then she went back inside.

She had a clock. Lancrastrians liked clocks, although they didn’t bother much about actual time in any length much shorter than an hour. If you needed to boil an egg, you sang fifteen verses of “Where Has All the Custard Gone?” under your breath. But the tick was a comfort on long evenings.

Finally she sat down in her rocking chair and glared at the doorway.

Owls were hooting in the forest when someone came running up the path and hammered on the door.

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

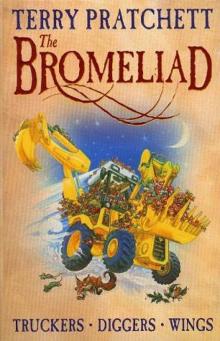

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II