- Home

- Terry Pratchett

Only You Can Save Mankind Page 10

Only You Can Save Mankind Read online

Page 10

They were all looking at him.

‘Anyway, that’s what I think,’ said Johnny.

Chapter 9

On Earth, No one Can Hear You

Say ‘Um’

Click!

‘Yes?’

‘Um.’

‘Hello?’

‘Um. Is Sig – is Kirsty there?’

’Who’s that?’

‘I’m a friend. Um. I don’t think she knows my name.’

‘You’re a friend and she doesn’t know your name?’

‘Please!’

‘Oh, hang on.’

Johnny stared at his bedroom wall. Eventually a suspicious voice said, ‘Yes? Who’s that?’

‘You’re Sigourney. You like C Inlay 4 Details. You fly really well. You—’

‘You’re him!’

Johnny breathed a sigh of relief. Real!

Going through the phone book had been harder than flying the starship. Nearly harder than dying.

‘I wasn’t sure you really existed,’ he said.

‘I wasn’t sure you existed,’ she said.

‘I’ve got to talk to you. I mean face to face.’

‘How do I know you’re not some sort of maniac?’

‘Do I sound like some sort of maniac?’

‘Yes!’

‘All right, but apart from that?’

There was silence for a moment. Then she said, reluctantly: ‘All right. You can come round here.’

‘What? To your house?’

‘It’s safer than in public, idiot.’

Not for me, Johnny thought.

‘OK,’ he said.

‘I mean, you might be one of those funny people.’

‘What, clowns?’

And then she said, very cautiously: ‘It’s really you?’

‘Really I’m not sure about. But me, yes.’

‘You got blown up.’

‘Yes, I know. I was there, remember.’

‘I don’t die often in the game. It took me ages even to find the aliens.’

Huh, thought Johnny.

‘It doesn’t get any better with practice,’ he said, darkly.

Tyne Crescent turned out to be a pretty straight road with trees in it, and the houses were big and had double garages and a timber effect on them to fool people into believing that Henry VIII had built them.

Kirsty’s mother opened the door for him. She was grinning like the Captain, although the Captain had the excuse that she was related to crocodiles. Johnny felt he had the wrong clothes on, or the wrong face.

He was shown into a large room. It was mainly white. Expensive bookshelves lined one wall. Most of the floor was bare pine, but varnished and polished to show that they could have afforded carpets if they’d wanted them. There was a harp standing by a chair in one corner, and music scattered around it on the floor.

Johnny picked up a sheet. It was headed ‘Royal College, Grade V’.

‘Well?’

She was standing behind him. The sheet slipped out of his fingers.

‘And don’t say “um”,’ she said, sitting down. ‘You say “um” a lot. Aren’t you ever sure about things?’

‘U— No. Hello?’

‘Sit down. My mother’s making us some tea. And then staying out of the way. You’ll probably notice that. You can actually hear her staying out of the way. She thinks I ought to have more friends.’

She had red hair, and the skinny look that went with it. It was as if someone had grabbed the frizzy ponytail on the back of her head and pulled it tightly.

‘The game,’ said Johnny vaguely.

‘Yes? What?’

‘I’m really glad you’re in it too. Yo-less said it was all in my head because of Trying Times. He said it was just me projecting my problems.’

‘I haven’t got any problems,’ snapped Kirsty. ‘I get on extremely well with people, actually. There’s probably some simple psychic reason that you’re too stupid to work out.’

‘You sounded more concerned on the phone,’ said Johnny.

‘But now I’ve had time to think about it. Anyway, what’s it to me what happens to some dots in a machine?’

‘Didn’t you see the Space Invaders?’ said Johnny.

‘Yes, but they were stupid. That’s what happens. Charles Darwin knew about that. I am a winning kind of person. And what I want to know is, what were you doing in my dream?’

‘I’m not sure it’s a dream,’ said Johnny. ‘I’m not sure what it is. Not exactly a dream and not exactly real. Something in between. I don’t know. Maybe something happens in your head. Maybe you’re in there because – because, well, I don’t know why, but there’s got to be a reason,’ he ended lamely.

‘Why’re you there, then?’

‘I want to save the ScreeWee.’

‘Why?’

‘Because . . . I’ve got a responsibility. But the Captain’s been . . . I don’t know, locked up or something. There’s been some kind of mutiny. It’s the Gunnery Officer. He’s behind it. But if I – if we could get her out, she could probably turn the fleet around again. I thought you might be able to think of some way of getting her out,’ Johnny finished lamely. ‘We haven’t got a lot of game time.’

‘She?’ said Kirsty.

‘She started all this. She relied on me,’ said Johnny.

‘You said “she”,’ said Kirsty.

Johnny stood up.

‘I thought you might be able to help,’ he said wearily, ‘but who cares what happens to some dots that aren’t even real. So I’ll just—’

‘You keep saying “she”,’ said Kirsty. ‘You mean the Captain’s a woman?’

‘A female,’ said Johnny. ‘Yes.’

‘But you called the Gunnery Officer a “he”,’ said Kirsty.

‘That’s right.’

Kirsty stood up.

‘That’s typical. That’s absolutely typical of modern society. He probably resents a wo— a female being better than him. I get that all the time.’

‘Um,’ said Johnny. He hadn’t meant to say ‘um’. He meant to say: ‘Actually, all the ScreeWee except the Gunnery Officer are females.’ But another part of his brain had thought faster and shut down his mouth before he could say it, diverting the words into oblivion and shoving good old ‘um’ in their place.

‘There was an article in a magazine,’ said Kirsty. ‘This whole bunch of directors of a company ganged up on this woman and sacked her just because she’d become the boss. It was just like me and the Chess Club.’

It probably wouldn’t be a good idea to tell her. There was a glint in her eye. No, it probably wouldn’t be a good idea to be honest. Truthfulness would have to do instead. After all, he hadn’t actually lied.

‘It’s a matter of principle,’ said Kirsty. ‘You should have said so right at the start.’ She stood up. ‘Come on.’

‘Where are we going?’ said Johnny.

‘To my room,’ said Kirsty. ‘Don’t worry. My parents are very liberal.’

There were film posters all over the walls, and where there weren’t film posters there were shelves with silver cups on. There was a framed certificate for the Regional Winner of the Small-Bore Rifle Confederation’s National Championships, and another one for chess. And another one for athletics. There were a lot of medals, mostly gold, and one or two silver. Kirsty won things.

If there was a medal for a tidy bedroom, she would have won that too. You could see the floor all the way to the walls.

She had an electrical pencil sharpener.

And a computer. The screen was showing the familiar message: NEW GAME (Y/N)?

‘Do you know I have an IQ of one hundred and sixty-five?’ she said, sitting down in front of the screen.

‘Is that good?’

‘Yes! And I only started playing this wretched game because my brother bought it and said I wouldn’t be any good at it. These things are moronic.’

There was a notebook by the keyboard.

‘Each level,’ explained Kirsty. ‘I made notes about how the ships flew. And kept score, of course.’

‘You were taking it seriously,’ said Johnny. ‘Very seriously.’

‘Of course I take it seriously. It’s a game. You’ve got to win them, otherwise what’s the point? Now . . . can we get on to the ScreeWee flagship?’

‘Um—’

‘Think!’

‘Can we get into a ScreeWee battleship?’

Kirsty almost growled. ‘I asked you. Sit down and think!’

Johnny sat down.

‘I don’t think we can,’ he said. ‘I’m always in a starship. I think things have to look like they do on the screen.’

‘Hmm. Makes some sort of sense, I suppose.’ Kirsty stuck a pencil in the sharpener, which whirred for a while. ‘And we don’t know what it looks like inside.’ Johnny stared at the wall. Among the items pinned over the bed was a card for winning the Under-7 Long Jump. She wins everything, he thought. Wow. She actually assumes she’s going to win. Someone who always thinks they’re going to win . . .

He stared up at the movie posters. There was one he’d seen many times before. The famous one. The slavering alien monster. You’d think she’d have something like a C Inlay 4 Details photo over her bed but no, there was this thing . . .

‘Don’t tell me,’ he said, ‘you want to get inside the ship and run along the corridors shooting ScreeWee? You do, don’t you?’

‘Tactically—’ she began.

‘You can’t. The Captain wouldn’t want that. Not killing ScreeWee.’

Kirsty waved her hands in the air irritably.

‘That’s stupid,’ she said. ‘How do you expect to win without killing the enemy?’

‘I’m supposed to save them. Anyway, they’re not exactly the enemy. I can’t go around killing them.’

Kirsty looked thoughtful.

‘Do you know,’ she said, ‘there was an African tribe once whose nearest word for “enemy” was “a friend we haven’t met yet”?’

Johnny smiled. ‘Right,’ he said. ‘That’s how—’

‘But they were all killed and eaten in eighteen hundred and two,’ said Kirsty. ‘Except for those who were sold as slaves. The last one died in Mississippi in eighteen sixty-four, and he was very upset.’

‘You just made that up,’ said Johnny.

‘No. I won a prize for History.’

‘I expect you did,’ said Johnny. ‘But I’m not killing anyone.’

‘Then you can’t win.’

‘I don’t want to win. I just don’t want them to lose.’

‘You really are a dweeb, aren’t you? How can anyone go through life expecting to lose all the time?’

‘Well, I’ve got to, haven’t I? The world is full of people like you, for a start.’

Johnny realized he was getting angry again. He didn’t often get angry. He just got quiet, or miserable. Anger was unusual. But when it came, it overflowed.

‘They tried to talk to you, and you didn’t even listen! You were the only other one that got that involved! You were so mad to win you slipped into game space! And you’d have been so much better at saving them than me! And you didn’t even listen! But I listened and I’ve spent a week trying to Save Mankind in my sleep! It’s always people like me that have to do stuff like that! It’s always the people who aren’t clever and who don’t win things that have to get killed all the time! And you just hung around and watched! It’s just like on the television! The winners have fun! Winner types never lose, they just come second! It’s all the other people who lose! And now you’re only thinking of helping the Captain because you think she’s like you! Well, I don’t bloody well care any more, Miss Clever! I’ve done my best! And I’m going to go on doing it! And they’ll all come back into game space and it’ll be just like the Space Invaders all over again! And I’ll be there every night!’

Her mouth was open.

There was a knock on the door and almost immediately, mothers being what they are, Kirsty’s mother pushed it open. She brought in a wide grin and a tray.

‘I’m sure you’d both like some tea,’ she said. ‘And—’

‘Yes, mother,’ said Kirsty, and rolled her eyes.

‘—there’s some macaroons. Have you found out your friend’s name now?’

‘John Maxwell,’ said Johnny.

‘And what do your friends call you?’ said Kirsty’s mother sweetly.

‘Sometimes they call me Rubber,’ said Johnny.

‘Do they? Whatever for?’

‘Mother, we were talking,’ said Kirsty.

‘Cobbers is on in a minute,’ said Kirsty’s mother. ‘I, er, shall watch it on the set in the kitchen, shall I?’

‘Goodbye,’ said Kirsty, meaningfully.

‘Um, yes,’ said her mother, and went out.

‘She dithers a lot,’ said Kirsty. ‘Fancy getting married when you’re twenty! A complete lack of ambition.’

She stared at Johnny for a while. He was keeping quiet. He’d been amazed to hear his own thoughts.

Kirsty coughed. She looked a little uncertain, for the first time since Johnny had met her.

‘Well,’ she said. ‘Uh. OK. And . . . we won’t be able to fight all the players when they get back to game space.’

‘No. There’s not enough missiles.’

‘Could we dream a few more?’

‘No. I thought of that. You get the ship you play with. I mean, we know it’s only got six missiles. I’ve tried dreaming more and it doesn’t work.’

‘Hmm. Interesting problem. Sorry,’ she added quickly, when she saw his expression.

Johnny stared at the movie posters. Sigourney! Games everywhere. Bigmac was a tough guy in his head, and this one kept sharp pencils and had to win everything and in her head shot aliens. Everyone had these pictures of themselves in their head, except him . . .

He blinked.

And now his head ached. There was a buzzing in his ears.

Kirsty’s face drifted towards him.

‘Are you all right?’

The headache was really bad now.

‘You’re ill. And you look all thin. When did you last eat?’

‘I dunno. Had something last night, I think.’

‘Last night? What about breakfast and lunch?’

‘Oh, well . . . you know . . . I kept thinking about . . .’

‘You’d better drink that tea and eat that macaroon. Phew. When did you last have a bath?’

‘It’s kind of . . .’

‘Good grief—’

‘Listen! Listen!’ It was important to tell her. He didn’t feel well at all.

‘Yes?’

‘We dream our way in,’ he said.

‘What are you talking about? You’re swaying!’

‘We go on to their ship!’

‘But we agreed we don’t know what it looks like inside!’

‘OK! Good! So we decide what it does look like inside, right?’

She tapped her pad irritably.

‘So what does it look like?’

‘I don’t know! The inside of a spaceship! Corridors and cabins and stuff like that. Nuts and bolts and panels and sliding doors. Scotsmen saying the engines canna tak’ it anymoore. Bright blue lights!’

‘Hmm. That’s what you think is inside spaceships, is it?’

Kirsty glared at him. She generally glared. It was her normal expression.

‘When we go to sleep . . . I mean, when I go to sleep . . . I’ll try and wake up inside the ship,’ he said.

‘How?’

‘I don’t know! By concentrating, I suppose.’

She leaned forward. For the first time since he’d met her, she looked concerned.

‘You don’t look capable of thinking straight,’ she said.

‘I’ll be all right.’

Johnny stood up.

Chapter 10

In Space, no one Is Listening Anyway

And woke up.

/> He was lying down on something hard. There was some sort of mesh just in front of his eyes. He stared at it for a while.

There was also a faint vibration in the floor, and a distant background rumbling.

He was obviously back in game space, but he certainly wasn’t in a starship . . .

The mesh moved.

The Captain’s face appeared over the mesh, upside down.

‘Johnny?’

‘Where am I?’

‘You appear to be under my bed.’

He rolled sideways.

‘I’m on your ship?’

‘Oh, yes.’

‘Right! Hah! I knew I could do it . . .’

He stood up, and looked around the cabin. It wasn’t very interesting. Apart from the bed, which was under something that looked like a sun-ray lamp, there was only a desk and something that was probably a chair if you had four back legs and a thick tail.

On the desk were half a dozen plastic aliens. There was also a cage with a couple of long-beaked birds in it. They sat side by side on their perch and watched Johnny with almost intelligent eyes.

Right. Sigourney was right. He did think better in game space. All the decisions seemed so much clearer.

OK. So he was on board. He’d rather hoped to be outside the cabin the Captain was locked in, but this was a start.

He stared at the wall. There was a grille.

‘What’s that?’ he said, pointing.

‘It is where the air comes in.’

Johnny pulled at the grille. There was no very obvious way of removing it. If it could be removed, the hole behind it was easily big enough for the Captain. Air ducts. Well, what did he expect?

‘We’ve got to get this off,’ he said. ‘Before something dreadful happens.’

‘We are imprisoned,’ said the Captain. ‘What more can happen that is dreadful?’

‘Have you ever heard the name . . . Sigourney?’ said Johnny cautiously.

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

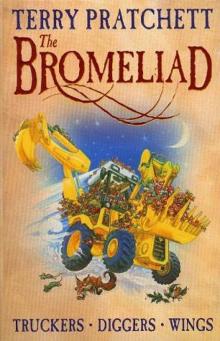

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II