- Home

- Terry Pratchett

Night Watch tds-27 Page 11

Night Watch tds-27 Read online

Page 11

“Knock it off, sarge, I'm not like that.”

“You were when you took that dollar. Everything else is just a haggling over the price.”

They walked in sullen silence. Then:

“Am I going to get the sack, sarge?” said the lance-constable.

“For a dollar? No.”

“I'd just as soon be sacked, sarge, thanks all the same,” said young Sam defiantly. “Last Friday we had to go and break up some meeting over near the University. They were just talking! And we had to take orders from some civilian, and the Cable Street lads were a bit rough and…it's not like the people had weapons or anything. You can't tell me that's right, sarge. And then we loaded some of 'em into the hurry-up, just for talking. Mrs Owlesly's boy Elson never came home the other night, too, and they say he was dragged off to the palace just for saying his lordship's a loony. Now people down our street are looking at me in a funny way.”

Ye gods, I remember, thought Vimes. I thought it was all going to be chasing men who gave up after the length of a street and said “It's a fair cop, guv'nor”. I thought I'd have a medal by the end of the week.

“You want to be careful what you say, lad,” he said.

“Yeah, but our mum says it's fair enough if they take away the troublemakers and the weirdies but it's not right them taking away ordinary people.”

Is this really me? Vimes thought. Did I really have the political awareness of a head louse?

“Anyway, he is a loony. Snapcase is the man we ought to have.”

…and the self-preservation instincts of a lemming?

“Kid, here's some advice. In this town, right now, if you don't know who you're talking to—don't talk.”

“Yes, but Snapcase says—”

“Listen. A copper doesn't keep flapping his lip. He doesn't let on what he knows. He doesn't say what he's thinking. No. He watches and listens and he learns and he bides his time. His mind works like mad but his face is a blank. Until he's ready. Understand?”

“All right, sarge.”

“Good. Can you use that sword you have there, lad?”

“I did the training, yes.”

“Fine. Fine. The training. Fine. So if we're attacked by a lot of sacks of straw hanging from a beam, I can rely on you. And until then shut up, keep your ears open and your eyes peeled and learn something.”

Snapcase is the man to save us, he thought glumly. Yeah, I used to believe that. A lot of people did. Just because he rode around in an open carriage occasionally and called people over and talked to them, the level of the conversation being on the lines of: “So you're a carpenter, are you? Wonderful! What does that job entail?” Just because he said publicly that perhaps taxes were a bit on the high side. Just because he waved.

“You been here before, sarge?” said Sam, as they turned a corner.

“Oh, everyone's visited Ankh-Morpork, lad,” said Vimes jovially.

“Only we're doing the Elm Street beat perfectly, sarge, and I've been letting you lead the way.”

Damn. That was the kind of trouble your feet could get you into. A wizard once told Vimes that there were monsters up near the Hub that were so big they had to have extra brains in their legs, 'cos they were too far away for one brain to think fast enough. And a beat copper grew brains in his feet, he really did.

Elm Street, left into The Pitts, left again into The Scours…it was the first beat he'd ever walked, and he could do it without thinking. He had done it without thinking.

“I do my homework,” he said.

“Did you recognize Ned?” said Sam.

Perhaps it was a good thing that he was leaving his feet to their own devices, because Vimes's brain suddenly filled with warning bells.

“Ned?” he said.

“Only before you came he said he thought he remembered you from Pseudopolis,” said Sam, oblivious of the clamour. “He was in the Day Watch there before he came here 'cos of better promotion prospects. Big man, he said.”

“Can't say I recall him,” said Vimes, with care.

“You're not all that big, sarge.”

“Well, Ned was probably shorter in those days,” said Vimes, while his thoughts shouted: shut up, kid! But the kid was…well, him. Niggling at little details. Tugging at things that didn't seem to fit right. Being a copper, in fact. Probably he ought to feel proud of his younger self, but he didn't.

You're not me, he thought. I don't think I was ever as young as you. If you're going to be me, it's going to take a lot of work. Thirty damn years of being hammered on the anvil of life, you poor bastard. You've got it all to come.

Back at the Watch House, Vimes wandered idly over to the Evidence and Lost Property cupboard. It had a big lock on it which was not, however, ever locked. He soon found what he was looking for. An unpopular copper needed to think ahead, and he intended to be unpopular.

Then he had a bite of supper and a mug of the thick brown cocoa on which the Night Watch ran and took Sam out on the hurry-up wagon.

He'd wondered how the Watch was going to play it and wasn't surprised to find they were using the old dodge of obeying orders to the letter with gleeful malignancy. At the first point he made, Lance-Corporal Coates and Constable Waddy were waiting with four sullen or protesting insomniacs.

“Four, sah,” said Coates, ripping off a textbook salute. “All we've apprehended sah. All written down on this chitty what I am giving to you at this moment in time sah!”

“Well done, lance-corporal,” said Vimes, drily, taking the paperwork, signing one copy and handing it back. “You may have a half-holiday at Hogswatch, and give my regards to your granny. Help 'em in with 'em, Sam.”

“We usually only get four or five on a round, sir!” Sam whispered, as they pulled away. “What'll we do?”

“Make several journeys,” said Vimes.

“But the lads were taking the pi—the michael, sir! They were laughing!”

“It's past curfew,” said Vimes. “That's the law.”

Corporal Colon and Constable Wiglet were waiting at their post with three miscreants.

One of them was Miss Palm.

Vimes gave Sam the reins and jumped down to open the back of the wagon and fold down the steps.

“Sorry to see you here, miss,” he said.

“Apparently some new sergeant's been throwing his weight around,” said Rosie Palm, in a voice of solid ice. She refused his hand haughtily, and climbed up into the wagon.

Vimes realized that one of the other detainees was a woman, too. She was shorter than Rosie, and was giving him a look of pure bantam defiance. She was also holding a huge quilted workbasket. Out of reflex Vimes took it, to help her up the steps.

“Sorry about this, miss—” he began.

“Get your hands off that!” She snatched the basket back and scrambled into the darkness.

“Pardon me,” said Vimes.

“This is Miss Battye,” said Rosie, from the bench inside the wagon. “She's a seamstress.”

“Well, I assumed she—”

“A seamstress, I said,” said Miss Palm. “With needles and thread. Also specializes in crochet.”

“Er, is that a kind of extra—” Vimes began.

“It's a type of knitting,” said Miss Battye, from the darkness of the wagon. “Fancy you not knowing that.”

“You mean she's a real–” said Vimes, but Rosie slammed the iron door. “You just drive us on,” she said, “and when I see you again, John Keel, we are going to have words!”

There was some sniggering from the shadows inside the wagon, and then a yelp. It had been immediately preceded by the noise of a spiky heel being driven into an instep.

Vimes signed the grubby form presented to him by Fred Colon and handed it back with a solid, fixed expression that made the man feel rather worried.

“Where to now, sarge?” said Sam, as they pulled away.

“Cable Street,” said Vimes. There was a murmur of dismay from the crated people behind them.

<

br /> “That's not right,” muttered Sam.

“We're playing this by the rules,” said Vimes. “You're going to have to learn why we have rules, lance-constable. And don't you eyeball me. I've been eyeballed by experts, and you look as if you're desperate for the privy.”

“Yeah, all right, but everyone knows they torture people,” mumbled Sam.

“Do they?” said Vimes. “Then why doesn't anyone do anything about it?”

“'cos they torture people.”

Ah, at least I was getting a grasp of basic social dynamics, thought Vimes.

Sullen silence reigned in the seat beside him as the wagon rumbled through the streets, but he was aware of whispering behind him. Slightly louder than the background, he heard Rosie Palm's voice hiss: “He won't. I'll bet anything.”

A few seconds later a male voice, slightly the worse for drink and very much the worse for bladder-twisting dread, managed:

“Er, sergeant, we…er…believe the fine is five, er, dollars?”

“I don't think it is, sir,” said Vimes, keeping his eyes on the damp streets.

There was some more frantic whispering, and then the voice said: “Er…I have a very nice gold ring.”

“Glad to hear it, sir,” said Vimes. “Everyone should have something nice,” He patted his pocket for his silver cigar case, and for a moment felt more anger than despair, and more sorrow than anger. There was a future. There had to be. He remembered it. But it only existed as that memory, and that was fragile as the reflection on a soap bubble and, maybe, just as easily popped.

“Er…I could perhaps include—”

“If you try to offer me a bribe one more time, sir,” said Vimes, as the wagon turned into Cable Street, “I shall personally give you a thumping. Be told.”

“Perhaps there is some other—” Rosie Palm began, as the lights of the Cable Street House came into view.

“We're not at home to a tuppenny upright, either,” said Vimes, and heard the gasp. “Shut up, the lot of you.”

He reined Marilyn to a halt, jumped down and pulled his clipboard from under the seat. “Seven for you,” he said, to the guard lounging against the door.

“Well?” said the guard. “Open it up and let's be having them, then.”

“Right,” said Vimes, flicking through the paperwork. “No problem.” He thrust the clipboard forward. “Just sign here.”

The man recoiled as though Vimes had tried to offer him a snake.

“What d'ya mean, sign?” he said. “Hand 'em over!”

“You sign,” said Vimes woodenly. “That's the rules. Prisoners moved from one custody to another, you have to sign. More'n my job's worth, not to get a signature.”

“Your job's not worth spit,” snarled the man, grabbing the board. He looked at it blankly, and Vimes handed him a pencil.

“If you need any help with the difficult letters, let me know,” he said helpfully.

Growling, the guard scrawled something on the paper and thrust it back.

“Now open up, p-lease,” he said.

“Certainly,” said Vimes, glancing at the paper. “But now I'd like to see some form of ID, thank you.”

“What?”

“It's not me, you understand,” said Vimes, “but if I went back and showed my captain this piece of paper and he said to me, Vi—Keel, how d'you know he's Henry the Hamster, well, I'd be a bit…flummoxed. Maybe even perplexed.”

“Listen, we don't sign for prisoners!”

“We do, Henry,” said Vimes. “No signature, no prisoners.”

“And you'll stop us taking 'em, will you?” said Henry the Hamster, taking a few steps forward.

“You lay a hand on that door,” said Vimes, “and I'll—”

“Chop it off, will you?”

“—I'll arrest you,” said Vimes. “Obstruction would be a good start, but we can probably think of some more charges back at the station.”

“Arrest me? But I'm a copper, same as you!”

“Wrong again,” said Vimes.

“What is thetrouble…here?” said a voice.

A small, thin figure appeared in the torchlight. Henry the Hamster took a step back, and adopted a certain deferential pose.

“Officer won't hand over the curfew breakers, sir,” he said.

“And this is the officer?” said the figure, lurching towards Vimes with a curiously erratic gait.

“Yessir.”

Vimes found himself under cool and not openly hostile inspection from a pale man with the screwed-up eyes of a pet rat.

“Ah,” said the man, opening a little tin and taking out a green throat pastille. “Would you be Keel, by anychance? I have been…hearing about you.” The man's voice was as uncertain as his walk. Pauses turned up in the wrong places.

“You hear about things quickly, sir.”

“A salute is generally in order, sergeant.”

“I don't see anything to salute, sir,” said Vimes.

“Goodpoint. Goodpoint. You are new, of course. But, you see, we in theParticulars…often find it necessary to wearplain…clothes.”

Like rubber aprons, if I recall correctly, thought Vimes. Aloud, he said: “Yes, sir.” It was a good phrase. It could mean any of a dozen things, or nothing at all. It was just punctuation until the man said something else.

“I'm Captain Swing,” said the man. “Findthee Swing. If you think the name is amusing, pleasesmirk…and get it over with. You may now salute.”

Vimes saluted. Swing's mouth turned up at the corners very briefly.

“Good. Your first night on our hurry-up wagon, sergeant?”

“Sir.”

“And you're here so early. With a full load, too. Shall we take alook…at your passengers?” He glanced in between the ironwork. “Ah. Yes. Good evening, Miss Palm. And an associate, I see—”

“I do crochet!”

“—and what appear to be some party-goers. Well, well.” Swing stood back. “What little scamps your street officers are, to be sure. They really have scoured the streets. How they love their…littlejokes, sergeant.” Swing put his hand on the wagon door's handle and there was a little noise which was nevertheless a thunderclap in the silence, and it was the sound of a sword moving very slightly in its scabbard.

Swing stood stock still for a moment and then delicately popped the pastille into his mouth. “Aha. I think that perhaps this little catch can be…thrownback, don't you, sergeant? We don't want to make a mockery of…thelaw. Take them away, take them away.”

“Yes, sir.”

“But just onemoment, please, sergeant. Indulge me…just a little hobby of mine

“Sir?”

Swing had reached into a pocket of his over-long coat and pulled out a very large pair of steel calipers. Vimes flinched as they were opened up to measure the width of his head, the width of his nose and the length of his eyebrows. Then a metal ruler was pressed against one ear.

While doing this, Swing was mumbling under his breath. Then he closed the calipers with a snap, and slipped them back.

“I must congratulateyou, sergeant,” he said, “in overcoming your considerable natural disadvantages. Do you know you have the eye of a mass murderer? I am neverwrong…in these matters.”

“Nosir. Didn't know that, sir. Will try to keep it closed, sir,” said Vimes. Swing didn't crack a smile.

“However, I'm sure that when you have settled in you and Corporal, aha, Hamster here will get along like a…houseonfire.”

“A house on fire. Yes, sir.”

“Don'tlet…me detain you, Sergeant Keel.”

Vimes saluted. Swing nodded, turned in one movement, as though he was on a swivel, and strode back into the Watch House. Or jerked, Vimes considered. The man moved in the same way he talked, in a curious mixture of speeds. It was as if he was powered by springs; when he moved a hand, the first few inches of movement were a blur, and then it gently coasted until it was brought into conjunction with whatever was the intended target. Sent

ences came out in spurts and pauses. There was no rhythm to the man.

Vimes ignored the fuming corporal and climbed back on to the wagon. “Turn us round, lance-constable,” he said. “G'night, Henry.”

Sam waited until the wheels were rumbling over the cobbles before he turned, wide-eyed, to Vimes.

“You were going to draw on him, weren't you?” he said. “You were, sarge, weren't you?”

“You just keep your eyes on the road, lance-constable.”

“But that was Captain Swing, that was! And when you told that man to prove he was Henry the Hamster, I thought I'd widd—choke! You knew they weren't going to sign, right, sarge? 'cos if there's a bit of paper saying they've got someone, then if anyone wants to find out—”

“Just drive, lance-constable.” But the boy was right. For some reason, the Unmentionables both loved and feared paperwork. They certainly generated a lot of it. They wrote everything down. They didn't like appearing on other people's paperwork, though. That worried them.

“I can't believe we got away with it, sarge!”

We probably haven't, Vimes thought. But Swing has enough to worry him at the moment. He doesn't care very much about a big stupid sergeant.

He turned and banged on the ironwork.

“Sorry for the inconvenience, ladies and gentlemen, but it appears the Unmentionables are not doing business tonight. Looks like we'll have to do the interrogation ourselves. We're not very experienced at this, so I hope we don't get it wrong. Now, listen carefully. Are any of you serious conspirators bent on the overthrow of the government?”

There was a stunned silence from within the wagon.

“Come on, come on,” said Vimes. “I haven't got all night. Does anyone want to overthrow Lord Winder by force?”

“Well…no?” said the voice of Miss Palm.

“Or by crochet?”

“I heard that!” said another female voice sharply.

“No one? Shame,” said Vimes. “Well, that's good enough for me. Lance-constable, is it good enough for you?”

“Er, yes, sarge.”

“In that case we'll drop you all off on our way home, and my charming assistant Lance-Constable Vimes will take, oh, half a dollar off each of you for travelling expenses for which you will get a receipt. Thank you for travelling with us, and we hope you will consider the hurry-up wagon in all your future curfew-breaking arrangements.”

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

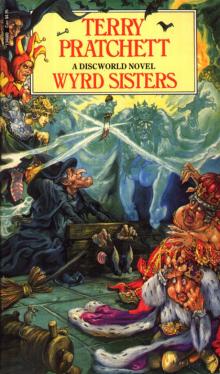

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

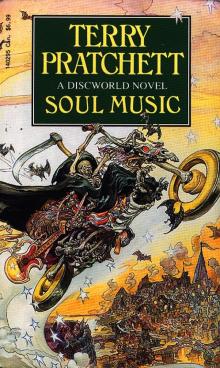

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

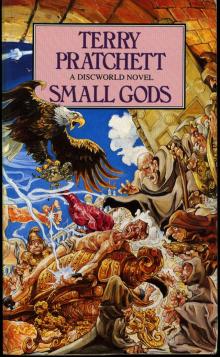

Soul Music Small Gods

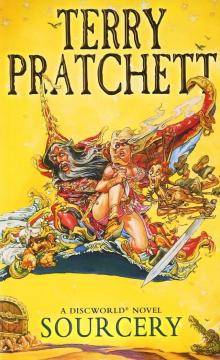

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

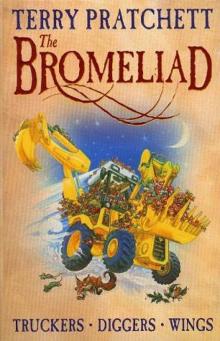

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II