- Home

- Terry Pratchett

Johnny and the Dead Page 12

Johnny and the Dead Read online

Page 12

‘Brought you your tray, Grandad.’

‘Right.’

‘You know the old cemetery? Where you showed me William Stickers’ grave?’

‘Right.’

‘Well, maybe it won’t be built on now. There was a meeting last night.’

‘Right?’

‘I spoke up at the meeting.’

‘Right.’

‘So it might be all right.’

‘Right.’

Johnny sighed. He went back into the kitchen.

‘Can I have an old sheet, Mum?’

‘What on earth for?’

‘Wobbler’s Halloween party. I can’t think of anything else.’

‘There’s the one I used as a dust cover, if you’re going to cut holes in it.’

‘Thanks, Mum.’

‘It’s pink.’

‘Aaaaooow, Mum!’

‘It’s practically washed out. No one’ll notice.’ It also, as it turned out, had the remains of some flowers embroidered on one end. Johnny did his best with a pair of scissors.

He’d promised he’d go. But he went the long way round, with the sheet in a bag, just in case the dead had come back and might see him. And there was Mr Grimm to think about now.

After he’d been gone a few minutes, the TV started showing the News in English, which looked less interesting than the Hindi News.

Grandad watched it for a while, and then sat up. ‘Hey, girl, it says they’re trying to save the old cemetery.’

‘Yes, Dad.’

‘It looked like our Johnny on the stage there.’

‘Yes, Dad.’

‘No one tells me anything around here. What’s this?’

‘Chicken, Dad.’

‘Right.’

They were somewhere in the high plateaus of Asia, where once camel trains had traded silk across five thousand miles and now madmen with guns shot one another in the various names of God.

‘How far to morning?’

‘Nearly there . . .’

‘What?’

The dead slowed down in a mountain pass, full of driving snow.

‘We owe the boy something. He took an interest. He remembered us.’

‘Zat’s absolutely correct. Conservation of energy. Besides, he’ll be worrying.’

‘Yes, but . . . if we go back now . . . we’ll become like we were, won’t we? I can feel the weight of that gravestone now.’

‘Sylvia Liberty! You said we shouldn’t leave!’

‘I’ve changed my mind, William.’

‘Yes. I spent half my life being frightened of dying, and now I’m dead I’m going to stop being frightened,’ said the Alderman. ‘Besides . . . I’m remembering things . . .’

There was a murmur from the rest of the dead.

‘I think ve all are,’ said Solomon Einstein. ‘All the zings we forgot when we were alive . . .’

‘That’s the trouble with life,’ said the Alderman. ‘It takes up your whole time. I mean, I won’t say it wasn’t fun. Bits of it. Quite a lot of it, really. In its own way. But it wasn’t what you’d call living . . .’

‘We don’t have to be frightened of the morning,’ said Mr Vicenti. ‘We don’t have to be frightened of anything.’

A skeleton opened the door.

‘It’s me, Johnny.’

‘It’s me, Bigmac. What’re you, a gay ghost?’

‘It’s not that pink.’

‘The flowers are good.’

‘Come on, let me in, it’s freezing out here.’

‘Can you float and mince at the same time?’

‘Bigmac!’

‘Come on, then.’

Somehow, it looked as if Wobbler hadn’t really put his heart into the decorations. There were a few streamers and some rubber spiders around the place, and a bowl of the dreadful punch you always get in these circumstances (the one with the brownish bits of orange in it) and bowls full of nibbles with names like Curly-Wigglies. And a vegetable marrow that looked as though it had walked into a combine harvester.

‘It was sposed to be a Jack-o’-Lantern,’ Wobbler kept telling everyone, ‘but I couldn’t find a pumpkin.’

‘Met Hannibal Lecter in a dark alley, did it?’ said Yo-less.

‘The plastic bats are good, aren’t they,’ said Wobbler. ‘They cost fifty pence each. Have some more punch?’

There were other people there, too, although in the semi-darkness it was hard to make out who they thought they were. There was someone with a lot of stitches and a bolt through his neck, but that was only Nodj, who looked like that anyway. There were a bunch from Wobbler’s computer group, who could get drunk on non-alcoholic alcohol and would then stagger around saying things like, ‘I’m totally mad!’ There were a couple of girls Wobbler vaguely knew. It was that sort of party. You just knew someone would put something daft in the punch, and everyone would talk about school, and one of the girls’ dads’d turn up at eleven o’clock and hang around looking determined and put a damper on things, as if they weren’t soaking wet already.

‘We could play a game,’ said Bigmac.

‘Not Dead Man’s Hand,’ said Wobbler. ‘Not after last year. You’re supposed to pass around grapes and stuff, not just anything you find in the fridge.’

‘It wasn’t what it was,’ said one of the girls. ‘It was what he said it was.’

‘All right,’ said Johnny to Yo-less, ‘I’ve been trying to work it out. Who are you?’

Yo-less had covered half his face with white make-up. He wasn’t wearing a shirt, just his ordinary string vest, but he’d found a piece of fake leopard-skin-pattern material which he’d draped over his shoulders. And he had a black hat.

‘Baron Samedi, the voodoo god,’ said Yo-less. ‘I got the idea out of James Bond.’

‘That’s racial stereotyping,’ someone said.

‘No, it’s not,’ said Yo-less. ‘Not if I’m doing it.’

‘I’m pretty sure Baron Samedi didn’t wear a bowler hat,’ said Johnny. ‘I’m pretty sure it was a top hat. A bowler hat makes you look a bit like you’re going to an office somewhere.’

‘I can’t help it, it was all I could get.’

‘Maybe he’s Baron Samedi, the voodoo god of chartered accountancy,’ said Wobbler.

For a moment Johnny thought of Mr Grimm; his face was all one colour, but he looked like a voodoo god of chartered accountancy if ever there was one.

‘In the film he was all mixed up with tarot cards and stuff,’ said Bigmac.

‘Not really,’ said Johnny, waking up. ‘Tarot cards are European occult. Voodoo is African occult.’

‘Don’t be daft, it’s American,’ said Wobbler.

‘No, American occult is Elvis Presley not being dead and that sort of thing,’ said Yo-less. ‘Voodoo is basically West African with a bit of Christian influence. I looked it up.’

‘I’ve got some ordinary cards,’ said Wobbler.

‘No messing around with cards,’ said Baron Yo-less severely. ‘My mum’d go spare.’

‘What about the thing with the letters and glasses?’

‘The postman?’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘No. That could lead to dark forces taking over, said Baron Yo-less. ‘It’s as bad as ouija boards.’

Someone put on a tape and started to dance. Johnny stared into his glass of horrible punch. There was an orange pip floating in it.

Cards and boards, he thought. And the dead. That’s not dark forces. Making a fuss about cards and heavy metal and going on about Dungeons and Dragons stuff because it’s got demon gods in it is like guarding the door when it is really coming up through the floorboards. Real dark forces . . . aren’t dark. They’re sort of grey, like Mr Grimm. They take all the colour out of life; they take a town like Blackbury and turn it into frightened streets and plastic signs and Bright New Futures and towers where no one wants to live and no one really does live. The dead seem more alive than us. And everyone becomes grey and

turns into numbers and then, somewhere, someone starts to do arithmetic . . .

The Demon God Yoth-Ziggurat might want to chop your soul up into little pieces, but at least he doesn’t tell you that you haven’t got one.

And at least you’ve got half a chance of finding a magic sword.

He kept thinking about Mr Grimm. Even the dead kept away from him.

He woke up to hear Wobbler say, ‘We could go Trick or Treating.’

‘My mother says that’s no better than begging,’ said Yo-less.

‘Hah, it’s worse than that around Joshua N’Clement,’ said Bigmac. ‘It’s called, “Giss five quid or kiss your tyres night-night”.’

‘We could do it around here,’ said Wobbler. ‘Or we could go down the mall.’

‘That’ll just be full of kids in costume running around screaming.’

‘A few more won’t hurt, then,’ said Johnny.

‘All right, then, everybody,’ Wobbler said. ‘Come on . . .’

In fact Neil Armstrong Mall was full of all the other people who’d run out of ideas at Halloween parties. They wandered around in groups looking at one another’s clothes and talking, which was pretty much what people did normally in any case, except that tonight the mall looked like Transylvania on late-shopping night.

Zombies lurched under the sodium lights. Witches walked around in groups and giggled at the boys. Grinning pumpkins bobbed on the escalators. Vampires gibbered among the sad indoor trees, and kept fumbling their false fangs back in. Mrs Tachyon rummaged for tins in the litter bins.

Johnny’s pink ghost outfit caused a lot of interest.

‘Seen any dead around lately?’ said Baron Yo-less, when Wobbler and Bigmac had gone off to buy some snacks.

‘Hundreds,’ said Johnny.

‘You know what I mean.’

‘No. Not them.’

‘I’m worried something may have happened to them.’

‘They’re dead. If they exist, that is,’ said Yo-less. ‘It’s not as though they could get run over or something. If you’ve saved their cemetery for them, they probably just aren’t bothering to talk to you any more. That’s probably what it is. I think—’

‘Anyone want a raspberry snake?’ said Wobbler, rustling a large paper bag. ‘The skulls are good, too.’

‘I’m going home,’ said Johnny. ‘There’s something wrong, and I don’t know what it is.’

A ten-year-old Bride of Dracula flapped past.

‘I’ve got to admit, this isn’t big fun,’ said Wobbler. ‘Tell you what . . . there’s Night of the Vampire Nerds on TV. We could go and watch that.’

‘What about everyone else?’ said Bigmac. The rest of the party had drifted off.

‘Oh, well, they know where I live,’ said Wobbler philosophically, as a blood-streaked ghoul went by eating an ice cream.

‘I don’t believe in vampire nerds,’ said Bigmac, as they stepped into the night air. It was a lot colder now, and the mist was coming back.

‘Oh, I dunno,’ said Wobbler. ‘It’s the sort we’d have round here.’

‘They’d suck fruit juice,’ said Yo-less.

‘Their mum’d make them go to bed late,’ said Bigmac, but they had to think about that.

‘Why are we going this way?’ said Wobbler. ‘This isn’t the way back.’

‘It’s foggy, too,’ said Bigmac.

‘It’s just the mist off the canal,’ said Johnny.

Wobbler stopped.

‘Oh, no,’ he said.

‘It’s quicker this way,’ said Johnny.

‘Oh, yes. Quicker. Oh, yes. Because I’m gonna run!’

‘Don’t be daft.’

‘It’s Halloween!’

‘So what? You’re dressed up as Dracula – what’re you worried about!’

‘I’m not going past there tonight!’

‘It’s no different than going past during the day.’

‘All right, it’s the same, but I’m different!’

‘Scared?’ said Bigmac.

‘What? Me? Scared? Huh? Me? I’m not scared.’

‘Actually, it is a bit risky,’ said Baron Yo-less.

‘Yes, risky,’ said Wobbler hurriedly.

‘I mean, you never know,’ said Yo-less.

‘Never know,’ Wobbler echoed.

‘Look, it’s a street in our town. There’s lights and a phone box and everything,’ said Johnny. ‘I just . . . I won’t be happy until I’ve checked, OK? Anyway, there’s four of us, after all.’

‘That just means something bad can happen four times,’ said Wobbler.

But they’d been walking as they talked; now the little light in the phone box loomed in the fog like a blurred star.

The other three went quiet. The fog hushed all sounds.

Johnny listened. There wasn’t even that blotting-paper silence that the dead made.

‘See?’ he whispered. ‘I said—’

Someone coughed, a long way off. All four boys suddenly tried to occupy the same spot.

‘Dead people don’t cough!’ hissed Johnny.

‘Then someone’s in the cemetery!’ said Yo-less.

‘Body snatchers!’ said Wobbler.

‘Burke ’n Head!’ said Bigmac.

‘I’ve read about this in the papers!’ whispered Wobbler. ‘People digging up graves for satanic rites!’

‘Shutup!’ said Johnny. They sagged. ‘Sounded to me like it came from the old boot factory,’ he said.

‘But it’s the middle of the night,’ said Yo-less.

They crept forward. There was a dim shape pulled on to the pavement where the streetlights barely shone.

‘It’s a van,’ said Johnny. ‘There. Count Dracula never drove a van.’

Bigmac tried to grin. ‘Unless he was a Vanpire—’

There was a metallic clink somewhere in the fog.

‘Wobbler?’ said Johnny, in what he hoped was a calm voice.

‘Yes?’

‘You said you were going to run. Go round to Mr Atterbury’s house right now and tell him to come here.’

‘What? By myself?’

‘You’ll run faster if you’re by yourself.’

‘Right!’

Wobbler gave them a frightened look and vanished.

‘What, exactly, are we doing?’ said Yo-less, as the other three peered into the fog.

There was no mistaking the noise this time. It was wrapped about with fog, but it was definitely the sound of a big diesel engine starting up.

‘Someone’s nicking a bulldozer!’ said Bigmac.

‘I wish that’s what they were doing,’ said Johnny, ‘but I don’t think they are. Come on, will you?’

‘Listen, if someone’s driving a bulldozer without lights in the fog, I’m not hanging around!’ said Yo-less.

Lights came on, fifty metres away. They didn’t show much. They just lit up two cones of fog.

‘Is that better?’ said Johnny.

‘No.’

The lights ground forward. The machine was bumping towards the cemetery railings. Old buddleia bushes and dead stinging nettles smashed under the treads, and there was a clang as the blade hit the low wall.

Johnny ran alongside the machine and shouted, ‘Oi!’

The engine stopped.

‘Run away!’ hissed Johnny to Yo-less. ‘Go on! Tell someone what’s happening!’

A man unfolded himself from the cab and jumped down. He advanced towards the boys, waving a finger.

‘You kids,’ he said, ‘are in real trouble.’

Johnny backed away, and someone grabbed his shoulders.

‘You heard the man,’ said a voice by his ear. ‘It’s your fault, this. So you’d better not have seen anything, right? Because we know where you live— Oh, no you don’t.’ A hand shot out and grabbed Yo-less as he tried to back away.

‘Know what I think?’ said the man who had been driving the bulldozer. ‘I think it’s lucky we happened to be passing and found ’em messing

around, eh? Shame they’d driven it right through the place already, eh? Kids today, eh?’

A half-brick sailed past Johnny’s face and hit the man beside him on the shoulder.

‘What the—’

‘I’ll smash your head in! I’ll smash your head in!’

Bigmac emerged from the fog. He looked terrifying. He reached beside him, yanked a railing from the broken wall and started to whirl it round his head as he advanced.

‘You what? You what? You what? I’m MENTAL, me!’

Then he started to run forward.

‘Aaaaaaarrrrrr—’

And it dawned on all four people at once that he wasn’t going to stop.

Chapter 10

Bigmac bounded over the rubble, an enraged skin head skeleton.

‘Get him!’

‘You get him!’

The railing smacked into the side of the bulldozer, and Bigmac leapt.

Even fighting mad, he was still Bigmac, and the driver was a large man. But what Bigmac had going for him was that he was, just for a few seconds, unstoppable. If the man had managed to get one good punch in that would have been it, but there seemed to be too many arms and legs in the way, and also Bigmac was trying to bite his ear.

Even so—

But a pair of headlights appeared near the gate and started to bounce up and down in a way that suggested a car being driven at high speed across rough ground.

The man holding Johnny let go and vanished into the fog. The other one thumped Bigmac hard in the stomach and followed him.

The car skidded to a halt and a fat vampire leapt out, shouting ‘Make my night, make my night!’

Mr Atterbury unfolded himself a little more sedately from the driver’s seat.

‘It’s all right, they’re gone,’ said Johnny. ‘We’ll never find them in this fog.

There was the sound of an engine starting somewhere in the distance, and then wheels skidded out on to the unseen road.

‘But I got the number!’ shouted Wobbler, hopping from foot to foot. ‘I dint have a pen so I huffed on the window and wrote it in the huff!’

‘They were going to drive the bulldozer into the cemetery!’ said Yo-less.

‘Right in the huff, look!’

‘Dear me, I expect a bit more than this of United Consolidated,’ said Mr Atterbury. ‘Hadn’t we better see to your friend?’

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

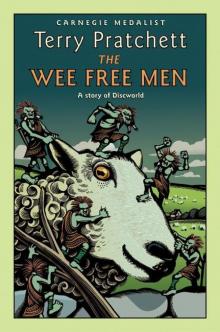

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

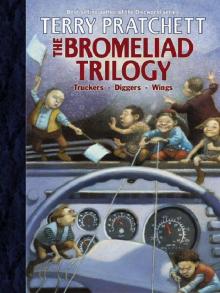

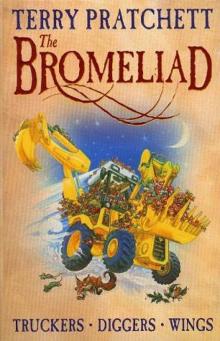

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

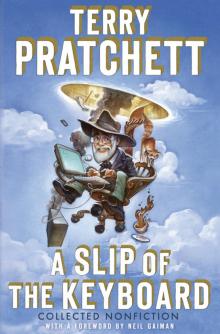

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

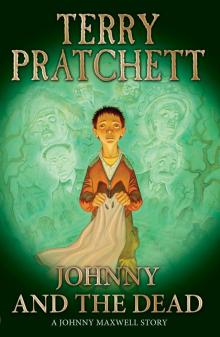

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II