- Home

- Terry Pratchett

Men at Arms tds-15 Page 17

Men at Arms tds-15 Read online

Page 17

“You dream of flying,” he said.

“Oh, yes. Then men would be truly free. From the air, there are no boundaries. There could be no more war, because the sky is endless. How happy we would be, if we could but fly.”

Vetinari turned the machine over and over in his hands.

“Yes,” he said, “I daresay we would.”

“I had tried clockwork, you know.”

“I'm sorry? I was thinking about something else.”

“I meant clockwork to power my flying machine. But it won't work.”

“Oh.”

“There's a limit to the power of a spring, no matter how tightly one winds it.”

“Oh, yes. Yes. And you hope that if you wind a spring one way, all its energies will unwind the other way. And sometimes you have to wind the spring as tight as it will go,” said Vetinari, “and pray it doesn't break.”

His expression changed.

“Oh dear,” he said.

“Pardon?” said Leonard.

“He didn't thump the wall. I may have gone too far.”

Detritus sat and steamed. Now he felt hungry—not for food, but for things to think about. As the temperature sank, the efficiency of his brain increased even more. It needed something to do.

He calculated the number of bricks in the wall, first in twos and then in tens and finally in sixteens. The numbers formed up and marched past his brain in terrified obedience. Division and multiplication were discovered. Algebra was invented and provided an interesting diversion for a minute or two. And then he felt the fog of numbers drift away, and looked up and saw the sparkling, distant mountains of calculus.

Trolls evolved in high, rocky and above all in cold places. Their silicon brains were used to operating at low temperatures. But down on the muggy plains the heat build-up slowed them down and made them dull. It wasn't that only stupid trolls came down to the city. Trolls who decided to come down to the city were often quite smart—but they became stupid.

Detritus was considered moronic even by city troll standards. But that was simply because his brain was naturally optimized for a temperature seldom reached in Ankh-Morpork even during the coldest winter…

Now his brain was nearing its ideal temperature of operation. Unfortunately, this was pretty close to a troll's optimum point of death.

Part of his brain gave some thought to this. There was a high probability of rescue. That meant he'd have to leave. That meant he'd become stupid again, as sure as

10-3(Me/Mp)a6aG-N = 10N.

Better make the most of it, then.

He went back to the world of numbers so complex that they had no meaning, only a transitional point of view. And got on with freezing to death, as well.

Dibbler reached the Butchers' Guild very shortly after Cuddy. The big red doors had been kicked open and a small butcher was sitting just inside them rubbing his nose.

“Which way did he go?”

“Dat way.”

And in the Guild's main hall the master butcher Gerhardt Sock was staggering around in circles. This was because Cuddy's boots were planted on his chest. The dwarf was hanging on to the man's vest like a yachtsman tacking into a gale, and whirling his axe round and round in front of Sock's face.

“You give it to me right now or I'll make you eat your own nose!”

A crowd of apprentice butchers was trying to keep out of the way.

“But—”

“Don't you argue with me! I'm an officer of the Watch, I am!”

“But you—”

“You've got one last chance, mister. Give it to me right now!”

Sock shut his eyes.

“What is it you want?”

The crowd waited.

“Ah,” said Cuddy. “Ahaha. Didn't I say?”

“No!”

“I'm pretty sure I did, you know.”

“You didn't!”

“Oh. Well. It's the key to the pork futures warehouse, if you must know.” Cuddy jumped down.

“Why?”

The axe hovered in front of his nose again.

“I was just asking,” said Sock, in a desperate and distant voice.

“There's a man of the Watch in there freezing to death,” said Cuddy.

There was quite a crowd around them when they finally got the main door open. Lumps of ice clinked on the stones, and there was a rush of supercold air.

Frost covered the floor and the rows of hanging carcasses on their backwards journey through time. It also covered a Detritus-shaped lump squatting in the middle of the floor.

They carried it out into the sunlight.

“Should his eyes be flashing on and off like that?” said Dibbler.

“Can you hear me?” shouted Cuddy. “Detritus?”

Detritus blinked. Ice slid off him in the day's heat.

He could feel the cracking up of the marvellous universe of numbers. The rising temperature hit his thoughts like a flamethrower caressing a snowflake.

“Say something!” said Cuddy.

Towers of intellect collapsed as the fire roared through Detritus' brain.

“Hey, look at this,” said one of the apprentices.

The inner walls of the warehouse were covered with numbers. Equations as complex as a neural network had been scraped in the frost. At some point in the calculation the mathematician had changed from using numbers to using letters, and then letters themselves hadn't been sufficient; brackets like cages enclosed expressions which were to normal mathematics what a city is to a map.

They got simpler as the goal neared—simpler, yet containing in the flowing lines of their simplicity a spartan and wonderful complexity.

Cuddy stared at them. He knew he'd never be able to understand them in a hundred years.

The frost crumbled in the warmer air.

The equations narrowed as they were carried on down the wall and across the floor to where the troll had been sitting, until they became just a few expressions that appeared to move and sparkle with a life of their own. This was maths without numbers, pure as lightning.

They narrowed to a point, and at the point was just the very simple symbol: “=”.

“Equals what?” said Cuddy. “Equals what?”

The frost collapsed.

Cuddy went outside. Detritus was now sitting in a puddle of water, surrounded by a crowd of human onlookers.

“Can't one of you get him a blanket or something?” he said.

A very fat man said, “Huh? Who'd use a blanket after it had been on a troll?”

“Hah, yes, good point,” said Cuddy. He glanced at the five holes in Detritus' breastplate. They were at about head height, for a dwarf. “Could you come over here for a moment, please?”

The man grinned at his friends, and sauntered over.

“I expect you can see the holes in his armour, right?” said Cuddy.

C. M. O. T. Dibbler was a survivor. In the same way that rodents and insects can sense an earthquake ahead of the first tremors, so he could tell if something big was about to go down on the street. Cuddy was being too nice. When a dwarf was nice like that, it meant he was saving up to be nasty later on.

“I'll just, er, go about my business, then,” he said, and backed away.

“I've got nothing against dwarfs, mind you,” said the fat man. “I mean, dwarfs is practically people, in my book. Just shorter humans, almost. But trolls… weeeelll… they're not the same as us, right?”

“'scuse me, 'scuse me, gangway, gangway,” said Dibbler, achieving with his cart the kind of getaway customarily associated with vehicles that have fluffy dice on the windscreen.

“That's a nice coat you've got there,” said Cuddy.

Dibbler's cart went around the corner on one wheel.

“It's a nice coat,” said Cuddy. “You know what you should do with a coat like that?”

The man's forehead wrinkled.

“Take it off right now,” said Cuddy, “and give it to the troll.”

“Wh

y, you little—”

The man grabbed Cuddy by his shirt and wrenched him upwards.

The dwarf's hand moved very quickly. There was a scrape of metal.

Man and dwarf made an interesting and absolute stationary tableau for a few seconds.

Cuddy had been brought up almost level with the man's face, and watched with interest as the eyes began to water.

“Let me down,” said Cuddy. “Gently. I make involuntary muscle movements if I'm startled.”

The man did so.

“Now take off your coat… good… just pass it over… thank you…”

“Your axe…” the man murmured.

“Axe? Axe? My axe?” Cuddy looked down. “Well, well, well. Hardly knew I was holding it there. My axe. Well, there's a thing.”

The man was trying to stand on tiptoe. His eyes were watering.

“The thing about this axe,” said Cuddy, “the interesting thing, is that it's a throwing axe. I was champion three years running up at Copperhead. I could draw it and split a twig thirty yards away in one second. Behind me. And I was ill that day. A bilious attack.”

He backed away. The man sank gratefully on to his heels.

Cuddy draped the coat over the troll's shoulders.

“Come on, on your feet,” he said. “Let's get you home.”

The troll lumbered upright.

“How many fingers am I holding up?” said Cuddy.

Detritus peered.

“Two and one?” he suggested.

“It'll do,” said Cuddy. “For a start.”

Mr Cheese looked over the bar at Captain Vimes, who hadn't moved for an hour. The Bucket was used to serious drinkers, who drank without pleasure but with a sort of determination never to see sobriety again. But this was something new. This was worrying. He didn't want a death on his hands.

There was no-one else in the bar. He hung his apron on a nail and hurried out towards the Watch House, ahnost colliding with Carrot and Angua in the doorway.

“Oh, I'm glad that's you, Corporal Carrot,” he said. “You'd better come. It's Captain Vimes.”

“What's happened to him?”

“I don't know. He's drunk an awful lot.”

“I thought he was off the stuff!”

“I think,” said Mr Cheese cautiously, “that this is not the case any more.”

A scene, somewhere near Quarry Lane: “Where we going?”

“I'm going to get someone to have a look at you.”

“Not dwarf doctor!”

“There must be someone up here who knows how to slap some quick-drying cement on you, or whatever you do. Should you be oozing like that?”

“Dunno. Never oozed before. Where we?”

“Dunno. Never been down here before.”

The area was on the windward side of the cattle yards and the slaughterhouse district. That meant it was shunned as living space by everyone except trolls, to whom the organic odours were about as relevant and noticeable as the smell of granite would be to humans. The old joke went: the trolls live next to the cattleyard? What about the stench? Oh, the cattle don't mind…

Which was daft. Trolls didn't smell, except to other trolls.

There was a slabby look about the buildings here. They had been built for humans but adapted by trolls, which broadly had meant kicking the doorways wider and blocking up the windows. It was still daylight. There weren't any trolls visible.

“Ugh,” said Detritus.

“Come on, big man,” said Cuddy, pushing Detritus along like a tug pushes a tanker.

“Lance-Constable Cuddy?”

“Yes.”

“You a dwarf. This is Quarry Lane. You found here, you in deep trouble.”

“We're city guards.”

“Chrysoprase, he not give a coprolith about that stuff.”

Cuddy looked around.

“What do you people use for doctors, anyway?”

A troll face appeared in a doorway. And another. And another.

What Cuddy had thought was a pile of rubble turned out to be a troll.

There were, suddenly, trolls everywhere.

I'm a guard, thought Cuddy. That's what Sergeant Colon said. Stop being a dwarf and start being a Watchman. That's what I am. Not a dwarf. A Watchman. They gave me a badge, shaped like a shield. City Watch, that's me. I carry a badge.

I wish it was a lot bigger.

Vimes was sitting quietly at a table in the corner of The Bucket. There were some pieces of paper and a handful of metal objects in front of him, but he was staring at his fist. It was lying on the table, clenched so tight the knuckles were white.

“Captain Vimes?” said Carrot, waving a hand in front of his eyes. There was no response.

“How much has he had?”

“Two nips of whiskey, that's all.”

“That shouldn't do this to him, even on an empty stomach,” said Carrot.

Angua pointed at the neck of a bottle protruding from Vimes' pocket.

“I don't think he's been drinking on an empty stomach,” she said. “I think he put some alcohol in it first.”

“Captain Vimes?” said Carrot again.

“What's he holding in his hand?” said Angua.

“I don't know. This is bad, I've never seen him like this before. Come on. You take the stuff. I'll take the captain.”

“He hasn't paid for his drink,” said Mr Cheese.

Angua and Carrot looked at him.

“On the house?” said Mr Cheese.

There was a wall of trolls around Cuddy. It was as good a choice of word as any. Right now their attitude was more of surprise than menace, such as dogs might show if a cat had just sauntered into the kennels. But when they'd finally got used to the idea that he really existed, it was probably only a matter of time before this state of affairs no longer obtained.

Finally, one of them said, “What dis, then?”

“He a man of the Watch, same as me,” said Detritus.

“Him a dwarf.”

“He a Watchman.”

“Him got bloody cheek, I know that.” A stubby troll finger prodded Cuddy in the back. The trolls crowded in.

“I count to ten,” said Detritus. “Then any troll not going about that troll's business, he a sorry troll.”

“You Detritus,” said a particularly wide troll. “Everyone know you stupid troll, you join Watch because stupid troll, you can't count to—”

Wham.

“One,” said Detritus. “Two… Tree. Four-er… Five. Six…”

The recumbent troll looked up in amazement.

“That Detritus, him counting.”

There was a whirring noise and an axe bounced off the wall near Detritus' head.

There were dwarfs coming up the street, with a purposeful and deadly air. The trolls scattered.

Cuddy ran forward.

“What are you lot doing?” he said. “Are you mad, or something?”

A dwarf pointed a trembling finger at Detritus.

“What's that?”

“He's a Watchman.”

“Looks like a troll to me. Get it!”

Cuddy took a step backwards and produced his axe.

“I know you, Stronginthearm,” he said. “What's this all about?”

“You know, Watchman,” said Stronginthearm. “The Watch say a troll killed Bjorn Hammerhock. They've found the troll!”

“No, that's not—”

There was a sound behind Cuddy. The trolls were back, armed for dwarf. Detritus turned around and waved a finger at them.

“Any troll move,” he said, “and I start counting.”

“Hammerhock was killed by a man,” said Cuddy. “Captain Vimes thinks—”

“The Watch have got the troll,” said a dwarf. “Damn rocks!”

“Gritsuckers!”

“Monoliths!”

“Eaters of rats!”

“Hah, I been a man only hardly any time,” said Detritus, “and already I fed up with you stupid trolls. Wha

t you think humans say, eh? Oh, them ethnic, them don't know how to behave in big city, go around waving clubs at the drop of a thing you wear on head.”

“We're Watchmen,” said Cuddy. “Our job is to keep the peace.”

“Good,” said Stronginthearm. “Go and keep it safe somewhere until we need it.”

“This not Koom Valley,” said Detritus.

“That's right!” shouted a dwarf at the back of the crowd. “This time we can see you!”

Trolls and dwarfs were pouring in at either end of the street.

“What would Corporal Carrot do at a time like this?” whispered Cuddy.

“He say, you bad people, make me angry, you stop toot sweet.”

“And then they'd go away, right?”

“Yeah.”

“What would happen if we tried that?”

“We look in gutter for our heads.”

“I think you're right.”

“You see that alley? It a nice alley. It say, hello. You outnumbered… 256+64+8+2+1 to 1. Drop in and see me.”

A club bounced off Detritus' helmet.

“Run!”

The two Watchmen sprinted for the alley. The impromptu armies watched them and then, differences momentarily forgotten, gave chase.

“Where this go?”

“It goes away from the people chasing us!”

“I like this alley.”

Behind them the pursuers, suddenly trying to make progress in a gap barely wide enough to accommodate a troll, realized that they were pushing and shoving with their mortal enemies and started to fight one another in the quickest, nastiest and above all narrowest battle ever held in the city.

Cuddy waved Detritus to a halt and peered around a comer.

“I think we're safe,” he said. “All we have to do is get out of the other end of this and get back to the Watch House. OK?”

He turned around, failed to see the troll, took a step forward, and vanished temporarily from the world of men.

“Oh, no,” said Sergeant Colon. “He promised he wasn't going to touch it any more! Look, he's had a whole bottle!”

“What is it? Bearhugger's?” said Nobby.

“Shouldn't think so, he's still breathing. Come on, help me up with him.”

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

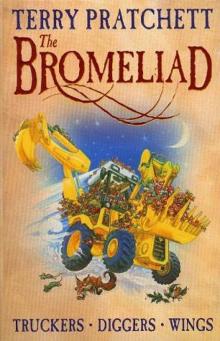

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II