- Home

- Terry Pratchett

The Science of Discworld II Page 2

The Science of Discworld II Read online

Page 2

+++ They were having such fun trying to send the bottle +++

‘Can’t you just bring them out, then?’

+++ Yes +++

‘In that case—’

‘Hold on,’ said Rincewind, remembering the blue beerbottle and the spelling mistakes. ‘Can you bring them out alive?’

Hex seemed affronted.

+++ Certainly. With a probability of 94.37 per cent +++

‘Not great odds,’ said Ponder, ‘But perhaps—’

‘Hold on again,’ said Rincewind, still thinking about that bottle. ‘Humans aren’t bottles. How about alive, with fully functioning brains and all organs and limbs in the right place?’

Unusually, Hex paused before replying.

+++ There will be unavoidable minor changes +++

‘How minor, exactly.’

+++ I cannot guarantee reacquiring more than one of every organ+++

There was a long, chilly silence from the wizards.

+++ Is this a problem? +++

‘Maybe there’s another way?’ said Rincewind.

‘What makes you think that?’

‘The note asks for the Librarian.’

In the heat of the night, magic moved on silent feet.

One horizon was red with the setting sun. This world went around a central star. The elves did not know this and, if they had done, it would not have bothered them. They never bothered with detail of that kind. The universe had given rise to life in many strange places, but the elves were not interested in that, either.

This world had created lots of life. Up until now, none of it had ever had what the elves considered to be potential. But this time, there was definite promise.

Of course, it had iron, too. The elves hated iron. But this time, the rewards were worth the risk. This time …

One of them signalled. The prey was close at hand. And now they saw it, clustered in the trees around a clearing, dark blobs against the sunset.

The elves assembled. And then, at a pitch so strange that it entered the brain without the need to use the ears, they began to sing.

1 And in this short statement may be seen the very essence of wizardly.

2 This one was apparently the result of a curse some 1,200 years ago by a dying Archchancellor, which sounded very much like ‘May you always teach fretwork!’

3 Lord Vetinari, the Patrician and supreme ruler of the city, took proper food labelling very seriously. Unfortunately, he sought the advice of the wizards of Unseen University on this one, and posed the question thusly: ‘Can you, taking into account multi-dimensional phase space, meta-statistical anomaly and the laws of probability, guarantee that anything with absolute certainty contains no nuts at all?’ After several days, they had to conclude that the answer was ‘no’. Lord Vetinari refused to accept ‘Probably does not contain nuts’ because he considered it unhelpful.

TWO

THE UMPTY-UMPTH ELEMENT

DISCWORLD RUNS ON MAGIC, Roundworld runs on rules, and even though magic needs rules and some people think rules are magical, they are quite different things. At least, in the absence of wizardly interference. This was the main scientific message of our last book, The Science of Discworld. There we charted the history of the universe from the Big Bang through to the creation of the Earth and the evolution of a not especially promising species of ape. The story ended with a final fast-forward to the collapse of the space elevator by which a mysterious race (which could not possibly have been those apes, who were only interested in sex and mucking about) had escaped from the planet. They had left the Earth because a planet is altogether too dangerous a place to live, and had headed out into the galaxy in search of safety and a long-term chance of a decent pint.

The Discworld wizards never found out who the builders of the space elevator on Roundworld were. We know that they were us, the descendants of those apes, who’d brought sex and mucking about to high levels of sophistication. The wizards missed that bit, although, to be fair, the Earth had been in existence for over four billion years, and apes and humans were present only for a tiny percentage of that time. If the entire history of the universe were compressed to one day, we would have been present for the final 20 seconds.

Quite a lot of interesting things happened on Roundworld while the wizards were skipping ahead, and now, in this present book, the wizards are going to find out what those things were. And of course they’re going to interfere, and inadvertently create the world we live in today, just as their interference in the Roundworld Project inadvertently created our entire universe. It has to work like that, doesn’t it?

That’s how the story goes.

Seen from outside, as it sits in Rincewind’s office, the entire human universe is a small sphere. Large quantities of magic went into its manufacture and, paradoxically, into maintaining its most interesting feature. Which is this: Roundworld is the only place on Discworld where magic does not work. A strong magical field protects it from the thaumic energies that surge around it. Inside Roundworld, things don’t happen because people want them to or because they make a good narrative: they happen because the rules of the universe, the so-called ‘laws of nature’, make them happen.

At least, that was a reasonable way to describe things … until human beings evolved. At that point, something very strange happened to Roundworld. It began, in various ways, to resemble Discworld. The apes acquired minds, and their minds started to interfere with the normal running of the universe. Things started to happen because human minds wanted them to. Suddenly the laws of nature, which up to that point had been blind, mindless rules, were infused with purpose and intention. Things started to happen for a reason, and among these things that happened was reasoning itself. Yet this dramatic change took place without the slightest violation of the same rules that had, up to that point, made the universe a place without purpose. Which, on the level of the rules, it still is.

This seems like a paradox. The main content of our scientific commentary, interleaved between successive episodes of a Discworld story, will be to resolve that paradox: how did Mind (capital ‘M’ for ‘metaphysical’) come into being on this planet? How did a Mindless universe ‘make up its own Mind’? How can we reconcile human free will (or its semblance) with the inevitability of natural law? What is the relation between the ‘inner world’ of the mind and the allegedly objective ‘outer world’ of physical reality?

The philosopher René Descartes argued that the mind must be built from some special kind of material – ‘mind-stuff’ that was different from ordinary matter, indeed undetectable using ordinary matter. Mind was an invisible spiritual essence that animated otherwise unthinking matter. It was a nice idea, because it explained at a stroke why Mind is so strange, and for a long time it was the conventional view. Nevertheless, today this concept of ‘Cartesian duality’ has fallen out of favour. Nowadays only cosmologists and particle physicists are allowed to invent new kinds of matter when they want to explain why their theories totally fail to match observed reality. When cosmologists find that galaxies are rotating at the wrong speeds in the wrong places, they don’t throw away their theories of gravitation. They invent ‘cold dark matter’ to fill in the missing 90 per cent of the mass of the universe. If any other scientists did that kind of thing, people would throw up their hands in horror and condemn it as ‘theory saving’. But cosmologists seem to get away with it.

One reason is that this idea has many advantages. Cold dark matter is cold, dark and material. Cold means that you can’t detect it by the heat radiation that it throws off, because it doesn’t. Dark means that you can’t detect it by the light that it emits, because it doesn’t. Matter means that it’s a perfectly ordinary material thing (not some silly invention like Descartes’ immaterial mind-stuff). Having said that, of course, cold dark matter is totally invisible, and it’s definitely not the same as conventional matter, which isn’t cold and isn’t dark …

To their credit, the cosmologists are trying very h

ard to find a way to detect cold dark matter. So far, they’ve discovered that it does bend light, so you can ‘see’ lumps of cold dark matter by the effect they have on images of more distant galaxies. Cold dark matter creates mirage-like distortions in the light from distant galaxies, smearing them out into thin arcs, centred on the lump of missing mass. From those distortions, astronomers can re-create the distribution of that otherwise invisible cold dark matter. The first results are coming in now, and within a few years it will be possible to survey the universe and find out whether the missing 90 per cent of matter really is there, cold and dark as expected, or whether the whole idea is nonsense.

Descartes’ similarly invisible, undetectable mind-stuff has had a very different history. At first, its existence seemed obvious: minds simply do not behave like the rest of the material world. Then, its existence seemed obvious nonsense, because you can chop a brain into pieces, preferably after ensuring that its owner has previously departed this world, and look for its material constituents. And when you do, there’s nothing unusual there. There’s lots of complicated proteins, arranged in very elaborate ways, but you won’t find a single atom of mind-stuff.2

We can’t yet dissect a galaxy, so for now cosmologists can get away with their absurd invention of a face-saving new material. Neuroscientists, trying to explain the mind, have no such luxury. Brains are much easier to pull apart than galaxies.

Despite the change in current conventional wisdom, there remain a few diehard dualists who still believe in special mind-stuff. But today, nearly all neuroscientists believe that the secret of Mind lies in the structure of the brain, and even more importantly, in the processes that the brain carries out. As you read these words, you experience a strong sense of Self. There is a You that is doing the reading, and thinking about the words and the ideas they express. No scientist has ever dissected out the bit of the brain that contains this impression of You. Most suspect that no such bit exists: instead, you feel like You because of the overall activity of your entire brain, plus the nerve fibres that are connected to it, bringing it sensations of the outside world and allowing it to control the movement of your arms, legs and fingers. You feel like you, in fact, because you are busily being You.

Mind is a process carried out within a brain made of perfectly ordinary matter, in accordance with the rules of physics. It is, however, a very strange process. There is a kind of duality, but it is a duality of interpretation rather than of physical material. When you think a thought – about, let us say, the Fifth Elephant that slipped off the back of Great A’Tuin, orbited in an arc of a circle and crashed on to the surface of the Discworld – the same physical act of thinking that thought has two distinct meanings.

One of them is straightforward physics. In your brain, various electrons are surging to and fro in various nerve fibres. Chemical molecules are combining together, or breaking up, to make new ones. Modern sensing apparatus, such as the PET scanner,1 can reconstruct a three-dimensional image of your brain, showing which regions are active when you are thinking about that elephant. Materially, your brain is buzzing in some complicated way. Science can see how it is buzzing, but it can’t (yet) extract the elephant.

That’s the second interpretation. From inside, so to speak, you have no sensation of those buzzing electrons and reacting chemicals. Instead, you have a very vivid impression of a large grey creature with flappy ears and a trunk, sailing improbably through space and crashing disastrously to the ground. Mind is what it feels like to be a brain. The same physical events acquire a totally different meaning when viewed from the inside. One task of science is to try to bridge the gap between those two interpretations. The first step is to figure out which bits of the brain do what when you think a particular thought. To reconstruct, in fact, the elephant from the electrons. That’s not yet possible, but every day brings it a step closer. Even when science gets there, it will probably not be able to explain why your impression of that elephant is so vivid, or why it takes exactly the form that it does.

In the study of consciousness there is a technical term for what a perception ‘feels like’. It is called a quale (pronounced ‘kwah-lay’, not ‘quail’), a figment that our minds paint on to their model of the universe in the way that an artist adds pigment to a portrait. Such qualia (plural) paint the world in vivid colours so that we can respond more quickly to it, and, in particular, respond to signs of danger, food, possible sexual partners … Science has no explanation of why qualia feel like they do, and it’s not likely to get one. So science can explain how a mind works, but not what it is like to be one. No shame in that: after all, physicists can explain how an electron works, but not what it is like to be one. Some questions are beyond science. And, we suspect, beyond anything else: it is easy enough to claim an explanation of these metaphysical problems, but just as impossible to prove you’re right. Science admits it can’t handle these things, so at least it’s honest.

At any rate, the science of the mind (small ‘M’ now because we’re not talking metaphysics) addresses how the mind works, and how it evolved, but not what it’s like to be one. Even with this limitation, the science of the brain is not the whole story. There is another important dimension to the question of Mind. Not how the brain works and what it does, but how it came to be like that.

How, on Roundworld, did Mind evolve from mindless creatures?

Much of the answer lies not inside the brain, but in its interactions with the rest of the universe. Especially other brains. Human beings are social animals, and they communicate with each other. The trick of communication made a huge, qualitative change to the evolution of the brain and its ability to house a mind. It accelerated the evolutionary process, because the transfer of ideas happens much faster than the transfer of genes.

How do we communicate? We tell stories. And that, we shall argue, is the real secret of Mind. Which brings us back to Discworld, because on Discworld things really do work the way human minds think they do on Roundworld. Especially when it comes to stories.

Discworld runs on magic, and magic is indissolubly linked to Narrative Causality, the power of story. A spell is a story about what a person wants to happen, and magic is what turns stories into reality. On Discworld, things happen because people expect them to. The sun comes up every day because that’s its job: it was set up to provide light for the people to see by, and it comes up during the day when people need it. That’s what suns do; that’s what they’re for. And it’s a proper, sensible sun, too: a smallish fire not very far away, which goes over and under the Disc, incidentally but entirely logically causing one of the elephants to lift a leg to let it pass. It’s not the ridiculous, pathetic kind of sun that we have – absolutely gigantic, infernally hot, and nearly a hundred million miles away because it’s too dangerous to be near. And we go round it instead of it going round us, which is crazy, especially since what every human being on the planet sees, other than the visually impaired, is the latter. It’s a terrible waste of material just to make daylight …

On Discworld, the eighth son of an eighth son must become a wizard. There’s no escaping the power of story: the outcome is inevitable. Even if, as in Equal Rites, the eighth son of an eighth son is a girl. Great A’Tuin the turtle must swim though space with four elephants on its back and the entire Discworld on top of them, because that’s what a world-bearing turtle has to do. The narrative structure demands it. Moreover, on Discworld everything that there is3 exists as a thing. To use the philosophers’ language, concepts are reified: made real. Death is not just a process of cessation and decay: he is also a person, a skeleton with a cloak and a scythe, and he TALKS LIKE THIS. On Discworld, the narrative imperative is reified into a substance, narrativium. Narrativium is an element, like sulphur or hydrogen or uranium. Its symbol ought to be something like Na, but thanks to a bunch of ancient Italians that’s already reserved for sodium (so much for So). So it’s probably Nv, or maybe Zq given what they’ve done to sodium. Be that as it may, narrativ

ium is an element on Discworld, so it lives somewhere in the Disc’s analogue of Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table. Where? The Bursar of Unseen University, the only wizard insane enough to understand imaginary numbers, would doubtless tell us that there is no question: it is the umpty-umpth element.

Discworld narrativium is a substance. It takes care of narrative imperatives, and ensures they are obeyed. On Roundworld, our world, humans act as if narrativium exists here, too. We expect it not to rain tomorrow because the village fair is on, and it would be unfair (in both senses) if rain spoiled the occasion.

Or, more often, given the pessimistic ways of our country folk, we expect it to rain tomorrow because the village fair is on. Most people expect the universe to be mildly malevolent but hope it will be kindly disposed, whereas scientists expect it to be indifferent. Drought-struck farmers pray for rain, in the express hope that the universe or owner thereof will hear their words and suspend the laws of meteorology for their benefit. Some, of course, actually believe just that, and for all anyone can prove, they could be right. This is a tricky question, and a delicate one; let us just say that no reputable scientific observer has yet caught God breaking the laws of physics (although of course He might be too clever for them) and leave it at that for the moment.

And this is where Mind takes centre stage.

The curious thing about the human belief in narrativium is that once humans evolved on the planet, their beliefs started to be true. We have, in a way, created our own narrativium. It exists in our minds, and there it is a process, not a thing. On the level of the material universe, it’s just one more pattern of buzzing electrons. But on the level of what it feels like to be a mind, it operates just like narrativium. Not only that: it operates on the material world, not just the mental one: its effects are just like those of narrativium. Generally our minds control our bodies – sometimes they don’t, and indeed sometimes it’s the other way round, especially during adolescence – and our bodies make things happen out there in the material world. Within each person there is a ‘strange loop’, which confuses the mental and material levels of existence.

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

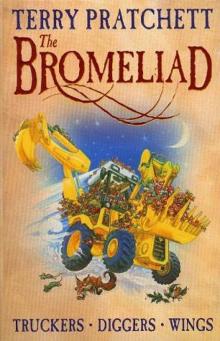

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II