- Home

- Terry Pratchett

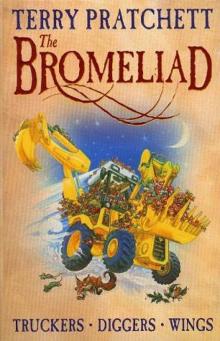

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers Page 3

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers Read online

Page 3

Several nomes had sleek rats on leads. Some of the ladies had mice, which trotted obediently behind them, and out of the corner of his ear Masklin could hear Granny Morkie tut-tutting her disapproval.

He also heard old Torrit say excitedly, 'I know that stuff! That's cheese! There was a cheese sandwich in the bin once, back in the summer of eighty-four, d'you remember-?' Granny Morkie nudged him hard in his skinny ribs.

'You shut up, you,' she commanded. 'You don't want to show us up in front of all these folk; do you? Be a leader. Act proud.' They weren't very good at it. They walked in stunned silence. Fruits and vegetables were &tacked behind trestle tables, with nomes working industriously on them. There were other things, too, which he couldn't begin to recognize. Masklin didn't want to show his ignorance, but curiosity got the better of him.

'What's that thing over there?' he said, pointing. 'It's a salami sausage,' said Angalo. 'Ever had it before?' 'Not lately,' said Masklin, truthfully.

'And they're dates,' said Angalo. 'And that's a banana. I expect you've never seen, a banana before, have you?' Masklin opened his mouth, but Granny Morkie beat him to it.

'Bit small, that one,' she said, and sniffed.

'Quite tiny, in fact, compared to the ones we got at home.' - 'It is, is it?' said Angalo, suspiciously.

'Oh, yes,' said Granny, beginning to warm to her subject. 'Very puny. Why, the ones we got at home,' she paused and looked at the banana, lying on a couple of trestles like a canoe, and her lips moved as she thought fast, 'why,' she added triumphantly, 'we could hardly dig them out o' the ground!' She stared victoriously at Angalo, who tried to outstare her and gave up.

'Well, whatever,' he said vaguely, looking away. 'You may all help yourselves. Tell the nomes in charge that it's to go on the Haberdasheri account, will you? But don't say you've come from Outside. I want that to be a surprise.' There was a general rush in the direction of the food. Even Granny Morkie just happened to wander towards it, and acted quite surprised to find her way blocked by a cake.

Only Masklin stayed where he was, despite the urgent complaints from his stomach. He wasn't sure he even began to understand how things worked in the Store, but he had an obscure feeling that if you didn't face them with dignity you could end up doing things you weren't entirely happy about.

'You're not hungry?' said Angalo.

'I'm hungry,' admitted Masklin, 'I'm just not eating. Where does all the food come from?' 'Oh, we take it from the humans,' said Angalo airily. 'They're rather stupid, you know.' 'And they don't mind?' 'They think it's rats,' sniggered Angalo. We take up rat doodahs with us. At least, the Food Hall families do,' he corrected himself. 'Sometimes they let other people go up with them. Then the humans just think it's rats.' Masklin's brow wrinkled.

'Doodahs?' he said.

'You know,' said Angalo. 'Droppings.' Masklin nodded. 'They fall for that, do they?' he said doubtfully.

'They're very stupid, I told you.' The boy walked around Masklin. 'You must come and see my father,' he said. 'Of course, it's a foregone conclusion that you'll join the Haberdasheri.' Masklin looked at the tribe. They had spread out among the food stalls. Torrit had a lump of cheese as big as his head, Granny Morkie was investigating a banana as if it might explode, and even Grimma wasn't paying him any attention.

Masklin felt lost. What he was good at, he knew, was tracking a rat across several fields, bringing it down with a single spear throw, and dragging it home. He'd felt really good about that People had said things like 'Well done'.

He had a feeling that you didn't have to track a banana. 'Your father?' he said.

'The Duke de Haberdasheri,' said Angalo proudly. 'Defender of the Mezzanine and Autocrat of the Staff Canteen.' 'He's three people?' said Masklin, puzzled.

'Those are his titles. Some of them. He's nearly the most powerful nome in the Store. Do you have things like fathers Outside?' Funny thing, Masklin thought. He's a rude little twerp except when he talks about the Outside, then he's like an eager little boy.

'I had one once,' he said. He didn't want to dwell on the subject.

'I bet you had- lots of adventures!' Masklin thought about some of the things that had happened to him - or, more accurately, had nearly happened to him - recently.

'Yes,' he said.

'I bet it was tremendous fun!' Fun, Masklin thought. It wasn't a familiar word. Perhaps it referred to running through muddy ditches with hungry teeth chasing you. 'Do you hunt?' he asked.

'Rats, sometimes. In the boiler-room. Of course, we have to keep them down.' He scratched Bobo behind an ear.

'Do you eat them?' Angalo looked horrified. 'Eat rat?' Masklin stared around at the piles of food. 'No, I suppose not,' he said. 'You know, I never realized there were so many nomes in the world. How many live here?' Angalo told him.

'Two what?' said Masklin.

Angalo repeated it.

'You don't look very impressed,' he said, when Masklin's expression didn't change.

Masklin looked hard at the end of his spear. It was a piece of flint he'd found in a field one day, and he'd spent ages teasing a bit of binder twine out of the haybale in order to tie it on to a stick. Right now it seemed about the one familiar thing in a bewildering world.

'I don't know,' he said. What is a thousand?' Duke Cido de Haberdasheri, who was also Lord Protector of the Up Escalator, Defender of the Mezzanine and Knight of the Counter, turned the Thing over in his hands, very slowly. Then he tossed it aside.

'Very amusing,' he said.

The nomes stood in a confused group in the Duke's palace, which was currently under the - floorboards in the Soft Furnishings Department. The Duke was still in armour, and not very amused.

'So,' he said, 'you're from Outside, are you? Do you really expect me to believe you?' 'Father, I-' Angalo began.

'Be quiet! You know the words of Arnold Bros (est. 1905)! Everything Under One Roof. Everything! Therefore, there can be no Outside. Therefore, you people are not from it. Therefore, you're from some other part of the Store. Corsetry. Or Young Fashions, maybe. We've never really explored there.' 'No, we're-' Masklin began.

The Duke held up his hands.

'Listen to me,' he said, glaring at Masklin. 'I don't blame you. My son is an impressionable young lad. I have no doubt he talked you into it. He's altogether too fond of going to look at lorries, and he listens to silly stories and his brain gets overheated. Now I am not an unreasonable nome,' he added, daring them to disagree, 'and there is always room for a strong lad like yourself in the Haberdashen guards. So let us forget this nonsense, shall we?' 'But we really do come from outside,' Masklin persisted.

'There is no Outside!' said the Duke. 'Except of course when a good nome dies, if he has led a proper life. Then there is an Outside, where they will live in splendour for ever. Come now,' he patted Masklin on the shoulder, 'give up this foolish chatter, and help us in our valiant task.' 'Yes, but what for?' said Masklin.

'You wouldn't want the Ironmongri to take our department, would you?' said the Duke. Masklin glanced at Angalo, who shook his head urgently.

'I suppose not,' he said, 'but you're all nomes, aren't you? And there's masses for everyone. Spending all your time squabbling seems a bit silly.' Out of the corner of his eye he saw Angalo put his head in his hands.

The Duke went red.

'Silly, did you say?' Masklin leaned backwards to get out of his-way, but he'd been brought up to be honest. He felt be wasn't bright enough to get away with lies.

Well-' he began.

'Have you never heard of honour?' said the Duke. Masklin thought for a while, and then shook his head.

'The Ironmongri want to take over the whole Store,' said Angalo hurriedly. 'That would be a terrible thing. And the Millineri are nearly as bad.' 'Why?' said Masklin.

'Why?' said the Duke 'Because they have always been our enemies. And now you may go,' he added.

'Where?' said Masklin.

'To the Ironmongri, or the Millineri.

Or the Stationeri, they're just the people for you. Or go back Outside, for all I care,' said the Duke sarcastically.

'We want the Thing back,' said Masklin stolidly.

The Duke picked it up and threw it at him.

'Sorry,' said Angalo, when they had got away.

'I should have told you father had rather a temper.' 'What did you go and upset him for?' said Grimma irritably. 'If we've got to- join up with someone, why not with him? What happens to us now?' 'He was very rude,' said Granny Morkie stoutly.

'He'd never heard of the Thing,' said Torrit. 'Terrible, that is. Or Outside. Well, I was borned and bred outside. Ain't no dead people there. Not living in any splendour, anyway.' They started to squabble, which was fairly usual. Masklin looked at them. Then he looked at his feet. They were walking on a sort of short dry grass that Angalo had said was called Carpet. Something else stolen from the Store above.

He wanted to say: this is ridiculous. Why is it that as soon as a nome has all he needs to eat and drink he starts to bicker with other nomes? There must be more to being a nome than this.

And he wanted to say: if humans are so stupid, how is it that they built this Store and all these lorries? If we're that clever, then they should be stealing from us, not the other way around. They might be big and slow, but they're quite bright, really.

And he wanted to add: I wouldn't be surprised if they're at least as intelligent as rats, say.

But he didn't say any of this, because while he was thinking his eyes fell on the Thing, clasped in Torrit's arms.

He was aware that there was a thought he ought to be having. He made a space in his head politely and waited patiently to see what it was and then, just as it was about to arrive, Grimma said to Angalo: 'What happens to nomes who aren't in a department?' 'They lead very sad lives,' said Angalo. 'They just have to get along as best they can.' He looked as if he was about to cry. 'I believe you,' he said. 'My father says it's wrong to watch the lorries. They can lead you into wrong thoughts, he says. Well, I've watched them for months. Sometimes they come in wet. It's not all a dream Outside, things happen. Look, why don't you sort of hang around, and I'm sure he'll change his mind.' The Store was big. Masklin had thought the lorry was big. The Store was bigger. It went on for ever, a maze of floor and walls and long, tiring steps. Nomes hurried or sauntered past them on errands of their own, and there seemed to be no end of them. In fact the word 'big' was too small. The Store needed a whole new word.

In a strange way it was even bigger than outside. Outside was so huge you didn't really see it. It had no edges and no top, so you didn't think of it as having a size at all. It was just there. Whereas the Store did have edges and a top, and they were so far away they were, well, big.

As they followed Angalo, Masklin made up his mind and decided to tell Grimma first.

'I'm going back,' he said. She stared at him. 'But we've only just arrived! Why on earth-?' 'I don't know. It's all wrong here. It just feels wrong. I keep thinking that if I stay here any longer I'll stop believing there's anything outside, and I was born there. When I've got you all settled down I'm going out again. You can come if you like,' he added, 'but you don't have to.' 'But it's warm and there's all this food!' 'I said I couldn't explain. I just feel we're being, well, watched.' Instinctively she stared upwards at the ceiling a few inches above them. Back home anything watching them usually meant something was thinking about lunch. Then she remembered herself, and gave a nervous laugh.

'Don't be silly,' she said.

'I just don't feel safe,' he said wretchedly.

'You mean you don't feel wanted,' said Grimma quietly.

'What?' 'Well, isn't that true? You spend all your time scrimping and scraping for everyone, and then you don't need to any more. It's a funny feeling, isn't it.' She swept away.

Masklin stood and fiddled with the binding on his spear. Odd, he thought. I never thought anyone else would think like that. He had a few dim recollections of Grimma in the hole, always doing laundry or organizing the old women or trying to cook whatever it was he managed to drag home. Odd. Fancy missing something like that.

He became aware that the rest of them had stopped. The underfloor stretched away ahead of them, lit dimly by small lights fixed to the wood here and there. Ironmongri charged highly for the lights, Angalo said, and wouldn't let anyone else into the secret of controlling the electric. It was one of the things that made the Ironmongri so powerful.

'This is the edge of Haberdasheri territory at the moment,' he said. 'Over there is Millineri country. We're a bit cool with them at the moment. Er. You're bound to find some department to take you in... 'He looked at Grimma.

'Er,' he said.

'We're going to stay together,' said Granny Morkie. She looked hard at Masklin, and then turned back imperiously and waved her hand at Angalo.

'Go away, young man,' she said. 'Masklin, stand up straight. Now... forward.' Who're you, saying forward?' said Torrit. 'I'm the leader, I am. It's my job, givin' orders.' 'All right,' said Granny Morkie. 'Give 'em, then.' Torrit's mouth worked soundlessly. 'Right,' he managed. 'Forward.' Masklin's jaw dropped.

'Where to?' he said, as the old woman shooed them along the dim space.

'We will find somewhere. I lived through the Great Winter of 1986,1 did,' said Granny Morkie haughtily. 'The cheek of that silly old Duke man! I nearly spoke up. He wouldn't of lasted long in the Great Winter, I can tell you.' 'No 'arm can befall us if we obey the Thing,' said Torrit, patting it carefully.

Masklin stopped. He had, he decided, had enough.

'What does the Thing say, then?' he said sharply. 'Exactly? What does it actually tell us to do now? Come on, tell me what it says we should do now!' Torrit looked a bit desperate. 'Er,' he began, 'It, er, is clear that if we pulls together and maintains a proper-' 'You're just making it up as you go along!' 'How date you speak to him like that-' Grimma began Masklin flung down his spear 'Well, I'm fed up with it!' he muttered. The Thing says this, the Thing says that, the Thing says every blessed thing except anything that might be useful!' The Thing has been handed down from nome to nome for hundreds of years,' said Grimma. 'It's very important.' 'Why?' Grimma looked at Torrit. He licked his lips.

'It shows us-' he began, white-faced.

'Move me closer to the electricity.' 'The Thing seems to be more important than what are you all looking like that for?' said Masklin.

'Closer to the electricity.' Torrit, his hands shaking, looked down at the Thing.

Where there had been smooth black surfaces there were now little dancing lights. Hundreds of them. In fact, Masklin thought, feeling slightly proud of knowing what the word meant, there were probably thousands of them.

'Who said that?' said Masklin.

The Thing dropped out of Torrit's grasp and landed on the floor, where its lights glittered like a thousand motorways at night. The nomes watched it in horror.

'The Thing does tell you things... 'said Masklin. 'Gosh!' Torrit waved his hands frantically. 'Not like that! Not like that! It ain't supposed to talk out loud! It's ain't done that before!' 'Closer to the electricity!' 'It wants the electricity,' said Masklin.

'Well, I'm not going to touch it!' Masklin shrugged and then, using his spear gingerly, pushed the Thing across the floor until it was under the wires. 'How does it speak? It hasn't got a mouth,' said Grimma.

The Thing whirred. Coloured shapes flickered across its surfaces faster than Masklin's eyes could follow. Most of them were red.

Torrit sank to his knees. 'It is angry,' he moaned. We shouldn't have eaten rat, we shouldn't have come here, we shouldn't-' Masklin also knelt down. He touched the bright areas, gingerly at first, but they weren't hot.

He felt that strange feeling again, of his mind wanting to think certain thoughts without having the right words.

'When the Thing has told you things before,' he said slowly, 'you know, how we should live proper lives-' Torrit gave him an agonized expression.

'It ne

ver has,' he said.

'But you said-' 'It used to, it used to,' moaned Torrit. 'When old Voozel passed it on to me he said it used to, but he said that hundreds and hundreds of years ago it just stopped.' What?' said Granny Morkie. 'All these years, my good man, you've been telling us that the Thing says this and the Thing says that and the Thing says goodness knows what.' Now Torrit looked like a very frightened, trapped animal. Well?' said the old woman, menacingly. 'Ahem,' said Torrit. 'Er. What old Voozel said was, think about what the Thing ought to say, and then say it. Keep people on the right path, sort of thing. Help them get to the Heavens. Very important, getting to the Heavens. The Thing can help you get there, he said. Most important thing about it.' 'What?' shouted Granny. 'That's what he told me to do. It worked, didn't it?' Masklin ignored them. The coloured lines moved over the Thing in hypnotic patterns. He felt that he ought to know what they meant. He was certain they meant something. Sometimes, on fine days back in the times when he didn't have to hunt every day, he'd climb further along the bank until he could look down on the place where the lorries parked. There was a big blue board there, with little shapes and pictures on it. And in the litter-bins the boxes and papers had more shapes and pictures on them; he remembered the long argument they'd had about the chicken boxes with the pictures of the old man with the big whiskers on them. Several nomes had insisted that this was a picture of a chicken, but Masklin had rather felt that humans didn't go around eating old men. There had to be more to it than that. Perhaps old men made chicken.

The Thing hummed again.

'Fifteen thousand years have passed,' it said. Masklin looked up at the others.

'You talk to it,' Granny ordered Torrit. The old man backed away.

'Not me! Not me! I dunno what to say!' he said. 'Well, I ain't!' snapped Granny. 'That's the leader's job, is that!' 'Fifteen thousand years have passed,' the Thing repeated.

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II