- Home

- Terry Pratchett

Men at Arms tds-15 Page 6

Men at Arms tds-15 Read online

Page 6

Four pillars of black granite held up the ceiling. They had been carved with the names of noted Assassins from history. Cruces had his desk foursquare between them. He was standing behind it, his expression almost as wooden as the desk.

“I want a roll-call,” he snapped. “Has anyone left the Guild?”

“No, sir.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“The guards on the roofs in Filigree Street say no-one came in or went out, sir.”

“And who's watching them?”

“They're watching one another, sir.”

“Very well. Listen carefully. I want the mess cleaned up. If anyone needs to go outside the building, I want everyone watched. And then the Guild is going to be searched from top to bottom, do you understand?”

“What for, doctor?” said a junior lecturer in poisons.

“For… anything that is hidden. If you find anything and you don't know what it is, send for a council member immediately. And don't touch it.”

“But doctor, all sorts of things are hidden—”

“This will be different, do you understand?”

“No, sir.”

“Good. And no-one is to speak to the wretched Watch about this. You, boy… bring me my hat.” Dr Cruces sighed. “I suppose I shall have to go and tell the Patrician.”

“Hard luck, sir.”

The captain didn't say anything until they were crossing the Brass Bridge.

“Now then, Corporal Carrot,” he said, “you know how I've always told you how observation is important?”

“Yes, captain. I have always paid careful attention to your remarks on the subject.”

“So what did you observe?”

“Someone'd smashed a mirror. Everyone knows Assassins like mirrors. But if it was a museum, why was there a mirror there?”

“Please, sir?”

“Who said that?”

“Down here, sir. Lance-Constable Cuddy.”

“Oh, yes. Yes?”

“I know a bit about fireworks, sir. There's a smell you get after fireworks. Didn't smell it, sir. Smelled something else.”

“Well… smelled, Cuddy.”

“And there were bits of burned rope and pulleys.”

“I smelled dragon,” said Vimes.

“Sure, captain?”

“Trust me.” Vimes grimaced. If you spent any time in Lady Ramkin's company, you soon found out what dragons smelled like. If something put its head in your lap while you were dining, you said nothing, you just kept passing it titbits and hoped like hell it didn't hiccup.

“There was a glass case in that room,” he said. “It was smashed open. Hah! Something was stolen. There was a bit of card in the dust, but someone must have pinched it while old Cruces was talking to me. I'd give a hundred dollars to know what it said.”

“Why, captain?” said Corporal Carrot.

“Because that bastard Cruces doesn't want me to know.”

“I know what could have blown the hole open,” said Angua.

“What?”

“An exploding dragon.”

They walked in stunned silence.

“That could do it, sir,” said Carrot loyally. “The little devils go bang at the drop of a helmet.”

“Dragon,” muttered Vimes. “What makes you think it was a dragon, Lance-Constable Angua?”

Angua hesitated. “Because a dog told me” was not, she judged, a career-advancing thing to say at this point.

“Woman's intuition?” she suggested.

“I suppose,” said Vimes, “you wouldn't hazard an intuitive guess as to what was stolen?”

Angua shrugged. Carrot noticed how interestingly her chest moved.

“Something the Assassins wanted to keep where they could look at it?” she said.

“Oh, yes,” said Vimes. “I suppose next you'll tell me this dog saw it all?”

“Woof?”

Edward d'Eath drew the curtains, bolted the door and leaned on it. It had been so easy!

He'd put the bundle on the table. It was thin, and about four feet long.

He unwrapped it carefully, and there… it… was.

It looked pretty much like the drawing. Typical of the man—a whole page full of meticulous drawings of crossbows, and this in the margin, as though it hardly mattered.

It was so simple! Why hide it away? Probably because people were afraid. People were always afraid of power. It made them nervous.

Edward picked it up, cradled it for a while, and found that it seemed to fit his arm and shoulder very snugly.

You're mine.

And that, more or less, was the end of Edward d'Eath. Something continued for a while, but what it was, and how it thought, wasn't entirely human.

It was nearly noon. Sergeant Colon had taken the new recruits down to the archery butts in Butts Treat.

Vimes went on patrol with Carrot.

He felt something inside him bubbling over. Something was brushing the tips of his corroded but nevertheless still-active instincts, trying to draw attention to itself. He had to be on the move. It was all that Carrot could do to keep up.

There were trainee Assassins in the streets around the Guild, still sweeping up debris.

“Assassins in daylight,” snarled Vimes. “I'm amazed they don't turn to dust.”

“That's vampires, sir,” said Carrot.

“Hah! You're right. Assassins and licensed thieves and bloody vampires! You know, this was a great old city once, lad.”

Unconsciously, they fell into step… proceeding.

“When we had kings, sir?”

“Kings? Kings? Hell, no!”

A couple of Assassins looked around in surprise.

“I'll tell you,” said Vimes. “A monarch's an absolute ruler, right? The head honcho—”

“Unless he's a queen,” said Carrot.

Vimes glared at him, and then nodded.

“OK, or the head honchette—”

“No, that'd only apply if she was a young woman. Queens tend to be older. She'd have to be a… a honcharina? No, that's for very young princesses. No. Um. A honchesa, I think.”

Vimes paused. There's something in the air in this city, he thought. If the Creator had said, “Let there be light” in Ankh-Morpork, he'd have got no further because of all the people saying “What colour?”

“The supreme ruler, OK,” he said, starting to stroll forward again.

“OK.”

“But that's not right, see? One man with the power of life and death.”

“But if he's a good man—” Carrot began.

“What? What? OK. OK. Let's believe he's a good man. But his second-in-command—is he a good man too? You'd better hope so. Because he's the supreme ruler, too, in the name of the king. And the rest of the court… they've got to be good men. Because if just one of them's a bad man the result is bribery and patronage.”

“The Patrician's a supreme ruler,” Carrot pointed out. He nodded at a passing troll. “G'day, Mr Carbuncle.”

“But he doesn't wear a crown or sit on a throne and he doesn't tell you it's right that he should rule,” said Vimes. “I hate the bastard. But he's honest. Honest like a corkscrew.”

“Even so, a good man as king—”

“Yes? And then what? Royalty pollutes people's minds, boy. Honest men start bowing and bobbing just because someone's grandad was a bigger murdering bastard than theirs was. Listen! We probably had good kings, once! But kings breed other kings! And blood tells, and you end up with a bunch of arrogant, murdering bastards! Chopping off queens' heads and fighting their cousins every five minutes! And we had centuries of that! And then one day a man said ‘No more kings!’ and we rose up and we fought the bloody nobles and we dragged the king off his throne and we dragged him into Sator Square and we chopped his bloody head off! Job well done!”

“Wow,” said Carrot. “Who was he?”

“Who?”

“The man who said ‘No More Kings’.”

People were staring. Vimes' face went from the red of anger to the red of embarrassment. There was little difference in the shading, however.

“Oh… he was Commander of the City Guard in those days,” he mumbled. “They called him Old Stoneface.”

“Never heard of him,” said Carrot.

“He, er, doesn't appear much in the history books,” said Vimes. “Sometimes there has to be a civil war, and sometimes, afterwards, it's best to pretend something didn't happen. Sometimes people have to do a job, and then they have to be forgotten. He wielded the axe, you know. No-one else'd do it. It was a king's neck, after all. Kings are,” he spat the word, “special. Even after they'd seen the… private rooms, and cleaned up the… bits. Even then. No-one'd clean up the world. But he took the axe and cursed them all and did it.”

“What king was it?” said Carrot.

“Lorenzo the Kind,” said Vimes, distantly.

“I've seen his picture in the palace museum,” said Carrot. “A fat old man. Surrounded by lots of children.”

“Oh yes,” said Vimes, carefully. “He was very fond of children.”

Carrot waved at a couple of dwarfs.

“I didn't know this,” he said. “I thought there was just some wicked rebellion or something.”

Vimes shrugged. “It's in the history books, if you know where to look.”

“And that was the end of the kings of Ankh-Morpork.”

“Oh, there was a surviving son, I think. And a few mad relatives. They were banished. That's supposed to be a terrible fate, for royalty. I can't see it myself.”

“I think I can. And you like the city, sir.”

“Well, yes. But if it was a choice between banishment and having my head chopped off, just help me down with this suitcase. No, we're well rid of kings. But, I mean… the city used to work.”

“Still does,” said Carrot.

They passed the Assassins' Guild and drew level with the high, forbidding walls of the Fools' Guild, which occupied the other corner of the block.

“No, it just keeps going. I mean, look up there.”

Carrot obediently raised his gaze.

There was a familiar building on the junction of Broad Way and Alchemists. The façade was ornate, but covered in grime. Gargoyles had colonized it.

The corroded motto over the portico said “NEITHER RAIN NOR SNOW NOR GLOM OF NIT CAN STAY THESE MESENGERS ABOT THIER DUTY” and in more spacious days that may have been the case, but recently someone had found it necessary to nail up an addendum which read:

DONT ASK US ABOUT:

rocks

troll's with sticks

All sorts of dragons

Mrs Cake

Huje green things with teeth

Any kinds of black dogs with orange eyebrows

Rains of spaniel's.

fog.

Mrs Cake

“Oh,” he said. “The Royal Mail.”

“The Post Office,” corrected Vimes. “My granddad said that once you could post a letter there and it'd be delivered within a month, without fail. You didn't have to give it to a passing dwarf and hope the little bugger wouldn't eat it before…”

His voice trailed off.

“Uh. Sorry. No offence meant.”

“None taken,” said Carrot cheerfully.

“It's not that I've got anything against dwarfs. I've always said you'd have to look very hard before you'd find a, a better bunch of highly skilled, law-abiding, hard-working—”

“—little buggers?”

“Yes. No!”

They proceeded.

“That Mrs Cake,” said Carrot, “definitely a strong-minded woman, eh?”

“Too true,” said Vimes.

Something crunched under Carrot's enormous sandal.

“More glass,” he said. “It went a long way, didn't it.”

“Exploding dragons! What an imagination the girl has.”

“Woof woof,” said a voice behind them.

“That damn dog's been following us,” said Vimes.

“It's barking at something on the wall,” said Carrot.

Gaspode eyed them coldly.

“Woof woof, bloody whine whine,” he said. “Are you bloody blind or what?”

It was true that normal people couldn't hear Gaspode speak, because dogs don't speak. It's a well-known fact. It's well known at the organic level, like a lot of other well-known facts which overrule the observations of the senses. This is because if people went around noticing everything that was going on all the time, no-one would ever get anything done.8 Besides, almost all dogs don't talk. Ones that do are merely a statistical error, and can therefore be ignored.

However, Gaspode had found he did tend to get heard on a subconscious level. Only the previous day someone had absent-mindedly kicked him into the gutter and had gone a few steps before they suddenly thought: I'm a bastard, what am I?

“There is something up there,” said Carrot. “Look… something blue, hanging off that gargoyle.”

“Woof woof, woof! Would you credit it?”

Vimes stood on Carrot's shoulders and walked his hand up the wall, but the little blue strip was still out of reach.

The gargoyle rolled a stony eye towards him.

“Do you mind?” said Vimes. “It's hanging on your ear…”

With a grinding of stone on stone, the gargoyle reached up a hand and unhooked the intrusive material.

“Thank you.”

“'on't ent-on it.”

Vimes climbed down again.

“You like gargoyles, don't you, captain,” said Carrot, as they strolled away.

“Yep. They may only be a kind of troll but they keep themselves to themselves and seldom go below the first floor and don't commit crimes anyone ever finds out about. My type of people.”

He unfolded the strip.

It was a collar or, at least, what remained of a collar—it was burnt at both ends. The word “Chubby” was just readable through the soot.

“The devils!” said Vimes. “They did blow up a dragon!”

The most dangerous man in the world should be introduced.

He has never, in his entire life, harmed a living creature. He has dissected a few, but only after they were dead,9 and had marvelled at how well they'd been put together considering it had been done by unskilled labour. For several years he hadn't moved outside a large, airy room, but this was OK, because he spent most of his time inside his own head in any case. There's a certain type of person it's very hard to imprison.

He had, however, surmised that an hour's exercise every day was essential for a healthy appetite and proper bowel movements, and was currently sitting on a machine of his own invention.

It consisted of a saddle above a pair of treadles which turned, by means of a chain, a large wooden wheel currently held off the ground on a metal stand. Another, freewheeling, wooden wheel was positioned in front of the saddle and could be turned by means of a tiller arrangement. He'd fitted the extra wheel and tiller so that he could wheel the entire thing over to the wall when he'd finished taking his exercise and, besides, it gave the whole thing a pleasing symmetry.

He called it “the-turning-the-wheel-with-pedals-and-another-wheel-machine”.

Lord Vetinari was also at work.

Normally, he was in the Oblong Office or seated in his plain wooden chair at the foot of the steps in the palace of Ankh-Morpork; there was an ornate throne at the top of the steps, covered with dust. It was the throne of Ankh-Morpork and was, indeed, made of gold. He'd never dreamed of sitting on it.

But it was a nice day, so he was working in the garden.

Visitors to Ankh-Morpork were often surprised to find that there were some interesting gardens attached to the Patrician's Palace.

The Patrician was not a gardens kind of person. But some of his predecessors had been, and Lord Vetinari never changed or destroyed anything if there was no logical reason to do so. He maintained the little zoo, and the racehorse s

table, and even recognized that the gardens themselves were of extreme historic interest because this was so obviously the case.

They had been laid out by Bloody Stupid Johnson.

Many great landscape gardeners have gone down in history and been remembered in a very solid way by the magnificent parks and gardens that they designed with almost god-like power and foresight, thinking nothing oi making lakes and shifting hills and planting woodlands to enable future generations to appreciate the sublime beauty of wild Nature transformed by Man. There have been Capability Brown, Sagacity Smith, Intuition De Vere Slade-Gore…

In Ankh-Morpork, there was Bloody Stupid Johnson.

Bloody Stupid “It Might Look A Bit Messy Now But Just You Come Back In Five Hundred Years' Time” Johnson. Bloody Stupid “Look, The Plans Were The Right Way Round When I Drew Them” Johnson. Bloody Stupid Johnson, who had 2,000 tons of earth built into an artificial hillock in front of Quirm Manor because “It'd drive me mad to have to look at a bunch of trees and mountains all day long, how about you?”

The Ankh-Morpork palace grounds were considered the high spot, if such it could be called, of his career. For example, they contained the ornamental trout lake, one hundred and fifty yards long and, because of one of those trifling errors of notation that were such a distinctive feature of Bloody Stupid's designs, one inch wide. It was the home of one trout, which was quite comfortable provided it didn't try to turn around, and had once featured an ornate fountain which, when first switched on, did nothing but groan ominously for five minutes and then fire a small stone cherub a thousand feet into the air.

It contained the hoho, which was like a haha only deeper. A haha is a concealed ditch and wall designed to allow landowners to look out across rolling vistas without getting cattle and inconvenient poor people wandering across the lawns. Under Bloody Stupid's errant pencil it was dug fifty feet deep and had claimed three gardeners already.

The maze was so small that people got lost looking for it.

But the Patrician rather liked the gardens, in a quiet kind of way. He had certain views about the mentality of most of mankind, and the gardens made him feel fully justified.

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

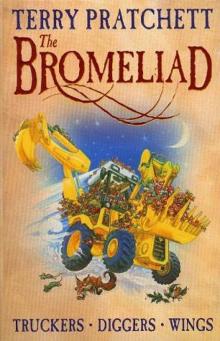

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II