- Home

- Terry Pratchett

Johnny and the Bomb Page 7

Johnny and the Bomb Read online

Page 7

He remembered touching a bag. Had time leaked out? Something had hissed through his fingers.

‘You can’t have the smallest possible particle of fridge! It’d just be iron atoms and so on!’

‘A fridge molecule, then. One atom of everything you need to make a fridge,’ said Yo-less.

‘You couldn’t ha— well, all right, you could have one atom of everything you need to make a fridge but that wouldn’t make it a fridge molecule because—’ She rolled her eyes. ‘What am I saying? You’ve got me thinking like that now!’

The rest of the universe said that time wasn’t an object, it was just Nature’s way of preventing everything from happening at once, and Mrs Tachyon had said: that’s what you think …

The path across the field led through the allotments. They looked like allotments everywhere, with the occasional old man who looked exactly like the old men who worked on allotments. They wore the special old man’s allotment trousers.

One by one, they stopped digging as the trolley bumped along the path. They turned and watched in a silent allotment way.

‘It’s probably Yo-less’s coat they’re looking at,’ Kirsty hissed. ‘Purple, green and yellow. It’s plastic, right? Plastic hasn’t been around for long. Of course, it might be Bigmac’s Heavy Mental T-shirt.’

They’re planting beans and hoeing potatoes, thought Johnny. And tonight there’s going to be a crop of great big bomb craters …

‘I can’t see the by-pass,’ said Bigmac. ‘And there’s no TV tower on Blackdown.’

‘There’s all those extra factory chimneys, though,’ said Yo-less. ‘I don’t remember any of those. And where’s the traffic noise?’

It’s May 21, 1941, thought Johnny. I know it.

There was a very narrow stone bridge over the river. Johnny stopped in the middle of it and looked back the way they’d come. A couple of the allotment men were still watching them. Beyond them was the sloping field they’d arrived in. It wasn’t particularly pretty. It had that slightly grey tint that fields get when they’re right next to a town and know that it’s only a matter of time before they’re under concrete.

‘I remember when all this was buildings,’ he said to himself.

‘What’re you going on about now?’

‘Oh, nothing.’

‘I recognize some of this,’ said Bigmac. ‘This is River Street. That’s old Patel’s shop on the corner, isn’t it?’ But the sign over the window said: *SMOKE WOODBINES* J. Wilkinson (prop.).

‘Woodbines?’ said Bigmac.

‘It’s a kind of cigarette, obviously,’ said Kirsty.

A car went past. It was black, but not the dire black of the one on the hill. It had mud and rust marks on it. It looked as though someone had started out with the idea of making a very large mobile jelly mould and had changed their mind about halfway through, when it was slightly too late. Johnny saw the driver crane his head to stare at them.

It was hard to tell much from the people on the streets. There were a lot of overcoats and hats, in a hundred shades of boredom.

‘We shouldn’t hang around,’ said Kirsty. ‘People are looking at us. Let’s go and see if we can get a newspaper. I want to know when we are. It’s so gloomy.’

‘Perhaps it’s the Depression,’ said Johnny. ‘My grandad’s always going on about when he was growing up in the Depression.’

‘No TV, everyone wearing old-fashioned clothes, no decent cars,’ said Bigmac. ‘No wonder everyone was depressed.’

‘Oh, God,’ said Kirsty. ‘Look, try to be careful, will you? Any little thing you do could seriously affect the future. Understand?’

They entered the corner shop, leaving Bigmac outside to guard the trolley.

It was dark inside, and smelled of floorboards.

Johnny had been on a school visit once, to a sort of theme park that showed you what things had been like in the all-purpose Olden Days. It had been quite interesting, although everyone had been careful not to show it, because if you weren’t careful they’d sneak education up on you while your guard was down. The shop was a bit like that, only it had things the school one hadn’t shown, like the cat asleep in the sack of dog biscuits. And the smell. It wasn’t only floorboards in it. There was paraffin in it, and cooking, and candles.

A small lady in glasses looked at them carefully.

‘Yes. What can I do for you?’ she said. She nodded at Yo-less.

‘Sambo’s with you, dear, is he?’ she added.

Chapter 6

The Olden Days

Guilty lay on top of the bags and purred.

Bigmac watched the traffic. There wasn’t a lot. A couple of women met one another as they were both crossing the street, and stood there chatting in the middle of the road, although occasionally one of them would turn to look at Bigmac.

He folded his arms over HEAVY MENTAL.

And then a car pulled up, right in front of him. The driver got out, glanced at Bigmac, and walked off down the street.

Bigmac stared at the car. He’d seen ones like it on television, normally in those costume dramas where one car and two women with a selection of different hats keep going up and down the same street to try to fool people that this isn’t really the present day.

The keys were still in the ignition.

Bigmac wasn’t a criminal, he was just around when crimes happened. This was because of stupidity. That is, other people’s stupidity. Mainly other people’s stupidity in designing cars that could go from 0–120mph in ten seconds and then selling them to even more stupid people who were only interested in dull things like fuel consumption and what colour the seats were. What was the point in that? That wasn’t what a car was for.

The keys were still in the ignition.

As far as Bigmac was concerned, he was practically doing people a favour by really seeing what their cars could do, and no way was that stealing, because he always put the cars back if he could and they were often nearly the same shape. You’d think people’d be proud to know their car could do 130mph along the Blackbury by-pass instead of complaining all the time.

The keys were still in the ignition. There were a million places in the world where the keys could have been, but in the ignition was where they were.

Old cars like this probably couldn’t go at any speed at all.

The keys were still in the ignition. Firmly, invitingly, in the ignition.

Bigmac shifted uncomfortably.

He was aware that there were people in the world who considered it wrong to take cars that didn’t belong to them but, however you looked at it …

… the keys were still in the ignition.

Johnny heard Kirsty’s indrawn breath. It sounded like Concorde taking off in reverse.

He felt the room grow bigger, rushing away on every side, with Yo-less all by himself in the middle of it.

Then Yo-less said, ‘Yes, indeed. I’m with them. Lawdy, lawdy.’

The old lady looked surprised.

‘My word, you speak English very well,’ she said.

‘I learned it from my grandfather,’ said Yo-less, his voice as sharp as a knife. ‘He ate only very educated missionaries.’

Sometimes Johnny’s mind worked fast. Normally it worked so slowly that it embarrassed him, but just occasionally it had a burst of speed.

‘He’s a prince,’ he said.

‘Prince Sega,’ said Yo-less.

‘All the way from Nintendo,’ said Johnny.

‘He’s here to buy a newspaper,’ said Kirsty, who in some ways did not have a lot of imagination.

Johnny reached into his own pocket, and then hesitated.

‘Only we haven’t got any money,’ he said.

‘Yes we have, I’ve got at least two pou—’ Kirsty began.

‘We haven’t got the right money,’ said Johnny meaningfully. ‘It was pounds and shillings and pence in those days, not pounds and pee—’

‘Pee?’ said the woman. She looked from one to the o

ther like someone who hopes that it’ll all make sense if they pay enough attention.

Johnny craned his head. There were a few newspapers still on the counter, even though it was the afternoon. One was The Times. He could just make out the date.

May 21, 1941.

‘Oh, you have a paper, dear,’ said the old woman, giving up, ‘I don’t suppose I shall sell any more today.’

‘Thank you very much,’ said Johnny, grabbing a paper and hurrying the other two out of the shop.

‘Sambo,’ said Yo-less, when they were outside.

‘What?’ said Kirsty. ‘Oh, that. Never mind about that. Give me that newspaper.

‘My grandad came here in 1952,’ said Yo-less, in the same plonking, hollow voice. ‘He said little kids thought his colour’d come off if he washed.’

‘Yes, well, I can see you’re upset, but that’s just how things were, it’s all changed since then,’ said Kirsty, turning the pages.

‘Then hasn’t even happened yet,’ said Yo-less. ‘I’m not stupid. I’ve read old books. We’re back in golliwog history. Plucky niggers and hooray for the Empire. She called me Sambo.’

‘Look,’ said Kirsty, still reading the newspaper. ‘This is the olden days. She didn’t mean it … you know, nastily. It’s just how she was brought up. You people can’t expect us to rewrite history, you know.’

Johnny suddenly felt as though he’d stepped into a deep freeze. It was almost certainly the you people. Sambo had been an insult, but you people was worse, because it wasn’t even personal.

He had never seen Yo-less so angry. It was a kind of rigid, brittle anger. How could someone as intelligent as Kirsty be so dumb? What she needed to do now was say something sensible.

‘Well, I’m certainly glad you’re here,’ said Yo-less, sarcasm gleaming on his words. ‘So’s you can explain all this to me.’

‘All right, don’t go on about it,’ she said, without looking up. ‘It’s not that important.’

It was amazing, Johnny thought. Kirsty had a sort of talent for striking matches in a firework factory.

Yo-less took a deep breath.

Johnny patted him on the arm.

‘She didn’t mean it … you know, nastily,’ he said. ‘It’s just how she was brought up.’

Yo-less sagged, and nodded coldly.

‘You know we’re in the middle of a war, don’t you,’ said Kirsty. ‘That’s what we’ve ended up in. World War Two. It was very popular around this time.’

Johnny nodded.

May the twenty-first, 1941.

Not many people cared or even knew about it now. Just him, and the librarian at the public library who’d helped him find the stuff for the project, and a few old people. It was ancient history, after all. The olden days. And here he was.

And so was Paradise Street.

Until tonight.

‘Are you all right?’ said Yo-less.

He hadn’t even known about it until he’d found the old newspapers in the library. It was – it was as if it hadn’t counted. It had happened, but it wasn’t a proper part of the war. And worse things had happened in a lot of other places. Nineteen people hardly mattered.

But he’d imagined it happening in his town. It was horribly easy.

The old men would go home from their allotments. The shops would shut. There wouldn’t be many lights in any case, because of the blackout, but bit by bit the town would go to sleep.

And then, a few hours later, it’d happen.

It’d happen tonight.

Wobbler wheezed along the road. And he did wobble. It wasn’t his fault he was fat, he’d always said, it was just his genetics. He had too many of them.

He was trying to run but most of the energy was getting lost in the wobbling.

He was trying to think, too, but it wasn’t happening very clearly.

They hadn’t gone time travelling! It was just a wind-up! They were always trying to wind him up! He’d get home and have a sit down, and it’d all be all right …

And this was home.

Sort of.

Everything was … smaller, somehow. The trees in the street were the wrong size and the cars were wrong. The houses looked … newer. And this was Gregory Road. He’d been along it millions of times. You went along halfway and turned into …

… into …

A man was clipping a hedge. He wore a high collar and tie and a pullover with a zig-zag pattern. He was also smoking a pipe. When he saw Wobbler he stopped clipping and took his pipe out of his mouth.

‘Can I help you, son?’ he said.

‘I … er … I was looking for Seeley Crescent,’ whispered Wobbler.

The man smiled.

‘Well, I’m Councillor Edward Seeley,’ he said, ‘but I’ve never heard of a Seeley Crescent.’ He called over his shoulder to a woman who was weeding a flowerbed. ‘Have you heard of a Seeley Crescent, Mildred?’

‘There’s a big chestnut tree on the corner—’ Wobbler began.

‘We’ve got a chestnut tree,’ said Mr Seeley, pointing to what looked like a stick with a couple of leaves on it. He smiled. ‘It doesn’t look much at the moment, but just you come back in fifty years’ time, eh?’

Wobbler stared at it, and then at him.

It was a wide garden here, with a field beyond it. It struck him that it was quite wide enough for a road, if … one day … someone wanted to build a road …

‘I will,’ he said.

‘Are you all right, young man?’ said Mrs Seeley.

Wobbler realized that he wasn’t panicking any more. He’d run out of panic. It was like being in a dream. Afterwards, it all sounded daft, but while you were in the dream you just got on with it.

It was like a rocket taking off. There was a lot of noise and worry and then you were in orbit, floating free, and able to look down on everything as if it weren’t real.

It was an amazing feeling. Wobbler had spent a large part of his life being frightened of things, in a vague kind of way. There were always things he should have been doing, or shouldn’t have done. But here it all didn’t seem to matter. He wasn’t even born yet – in a way, anyway – so absolutely nothing could be his fault.

‘I’m fine,’ he said. ‘Thank you very much for asking. I’ll … just be off back into town.’

He could feel them watching him as he wandered back down the road.

This was his home town. There were all sorts of clues that told him so. But all sorts of other things were … strange. There were more trees and fewer houses, more factory chimneys and fewer cars. A lot less colour, too. It didn’t look much fun. He was pretty certain no one here would even know what a pizza was—

‘’Ere, mister,’ said a hoarse voice.

He looked down.

A boy was sitting by the side of the road.

It was almost certainly a boy. But its short trousers reached almost to its ankles, it had a pair of glasses with one lens blanked out with brown paper, its hair had been cut apparently with a lawnmower, and its nose was running. And its ears stuck out.

No one had ever called Wobbler ‘mister’ before, except teachers when they wanted to be sarcastic.

‘Yes?’ he said.

‘Which way’s London?’ said the boy. There was a cardboard suitcase next to him, held together with string.

Wobbler thought for a moment. ‘Back that way,’ he said, pointing. ‘Dunno why there’s no road signs.’

‘Our Ron says they took ’em all down so Jerry wun’t know where he was,’ said the boy. He had a line of small stones on the kerb beside him. Every so often he’d pick one up and throw it with great accuracy at a tin can on the other side of the road.

‘Who’s Jerry?’

One eye looked at him with deep suspicion.

‘The Germans,’ said the boy. ‘Only I wants ’em to come here and blow up Mrs Density a bit.’

‘Why? Are we fighting the Germans?’ said Wobbler.

‘Are you ’n American? Our dad say

s the Americans ought to fight, only they’re waitin’ to see who’s winnin’.’

‘Er …’ Wobbler decided it might be best to be American for a bit. ‘Yes. Sure.’

‘Garn! Say something American!’

‘Er … right on. Republican. Microsoft. Spiderman. Have a nice day.’

This demonstration of transatlantic origins seemed to satisfy the small boy. He threw another stone at the tin can.

‘Our mam said I’ve got to stop along of Mrs Density’s and the food’s all rubbish,’ said the boy. ‘You know what, she makes me drinks milk! I dint mind the proper milk at home but round here, you know what, it comes out of a cow’s bum. I seen it. They took us to a farm with all muck all over the place and, you know what, you know how eggs come out? Urrr! And she makes us go to bed at seven o’clock and I miss our mam and I’m going home. I’ve had enough of being ’vacuated!’

‘It can really make your arm ache,’ said Wobbler. ‘I had it done for tetanus.’

‘Our Ron says it’s good fun, going down the Underground station when the siren goes off,’ the boy went on. ‘Our Ron says the school got hit an’ none of the kids has to go any more.’

It seemed to Wobbler that it didn’t matter what he said. The boy was really talking to himself. Another stone turned the can upside down.

‘Huh,’ said the boy. ‘Like to see ’em hit the school here. They just pick on us just ’cos we’re from London and, you know what, that Atterbury kid pinched my piece of shrapnel! Our Ron give it me. Our Ron’s a copper, he gets a chance to pick up really good stuff for me. You don’t get shrapnel round here, huh!’

‘What’s shrapnel?’ said Wobbler.

‘Are you a loony? It’s bits of bomb! Our Ron says Alf Harvey got a whole collection an’ a bit off’f a Heinkel. Our Ron said Alf Harvey found a real Nazi ring with an actual finger still in it.’ The boy looked wistful, as though unfairly shut off from untold treasures. ‘Huh! Our Ron says other kids down our street have gone back home and I reckon I’m old enough, too, so I’m goin’.’

Wobbler had never bothered much with history. As far as he was concerned it was something that had happened to other people.

He vaguely remembered a TV programme with some film shot back in the days when people were so poor they could only afford to be in black and white.

Feet of Clay

Feet of Clay The Color of Magic

The Color of Magic Thud!

Thud! Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch I Shall Wear Midnight

I Shall Wear Midnight Mort

Mort Raising Steam

Raising Steam Guards! Guards!

Guards! Guards! Equal Rites

Equal Rites A Hat Full of Sky

A Hat Full of Sky The Light Fantastic

The Light Fantastic Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook Wyrd Sisters

Wyrd Sisters Soul Music

Soul Music Small Gods

Small Gods Sourcery

Sourcery Reaper Man

Reaper Man Night Watch

Night Watch Lords and Ladies

Lords and Ladies The Fifth Elephant

The Fifth Elephant Monstrous Regiment

Monstrous Regiment The Truth

The Truth Witches Abroad

Witches Abroad Eric

Eric Going Postal

Going Postal Men at Arms

Men at Arms Jingo

Jingo The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents The Wee Free Men

The Wee Free Men Pyramids

Pyramids Wintersmith

Wintersmith Moving Pictures

Moving Pictures Carpe Jugulum

Carpe Jugulum Interesting Times

Interesting Times Maskerade

Maskerade Making Money

Making Money The Shepherd's Crown

The Shepherd's Crown Hogfather

Hogfather Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge The Last Continent

The Last Continent The Sea and Little Fishes

The Sea and Little Fishes Snuff

Snuff Unseen Academicals

Unseen Academicals Guards! Guards! tds-8

Guards! Guards! tds-8 Jingo d-21

Jingo d-21 Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far

Turtle Recall: The Discworld Companion ... So Far The Fifth Elephant d-24

The Fifth Elephant d-24 Discworld 39 - Snuff

Discworld 39 - Snuff The Long War

The Long War Only You Can Save Mankind

Only You Can Save Mankind The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3

The Science of Discworld III - Darwin's Watch tsod-3 A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction

A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction Unseen Academicals d-37

Unseen Academicals d-37 Wings

Wings Making Money d-36

Making Money d-36 A Blink of the Screen

A Blink of the Screen Johnny and the Bomb

Johnny and the Bomb Dodger

Dodger Strata

Strata Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic

Discworld 02 - The Light Fantastic The Folklore of Discworld

The Folklore of Discworld The Science of Discworld

The Science of Discworld The Unadulterated Cat

The Unadulterated Cat Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels)

Raising Steam: (Discworld novel 40) (Discworld Novels) The World of Poo

The World of Poo Discworld 05 - Sourcery

Discworld 05 - Sourcery The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories

The Witch's Vacuum Cleaner: And Other Stories The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2

The Science of Discworld II - The Globe tsod-2 Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A

Small Gods: Discworld Novel, A Men at Arms tds-15

Men at Arms tds-15 Tama Princes of Mercury

Tama Princes of Mercury The Last Hero (the discworld series)

The Last Hero (the discworld series) The Long Utopia

The Long Utopia Discworld 03 - Equal Rites

Discworld 03 - Equal Rites Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld

Terry Pratchett - The Science of Discworld The Long Earth

The Long Earth The Carpet People

The Carpet People The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld)

The Sea and Little Fishes (discworld) The Colour of Magic

The Colour of Magic Discworld 16 - Soul Music

Discworld 16 - Soul Music The Long Cosmos

The Long Cosmos The Dark Side of the Sun

The Dark Side of the Sun Monstrous Regiment tds-28

Monstrous Regiment tds-28 The Bromeliad 3 - Wings

The Bromeliad 3 - Wings Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories

Dragons at Crumbling Castle: And Other Stories Night Watch tds-27

Night Watch tds-27 The Science of Discworld I tsod-1

The Science of Discworld I tsod-1 The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers

The Bromeliad 1 - Truckers The Science of Discworld Revised Edition

The Science of Discworld Revised Edition The Abominable Snowman

The Abominable Snowman Father Christmas’s Fake Beard

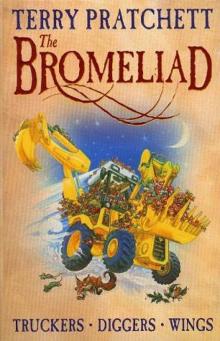

Father Christmas’s Fake Beard The Bromeliad Trilogy

The Bromeliad Trilogy A Slip of the Keyboard

A Slip of the Keyboard The Wee Free Men d(-2

The Wee Free Men d(-2 Johnny and the Dead

Johnny and the Dead Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels)

Mrs Bradshaw's Handbook (Discworld Novels) Truckers

Truckers The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1

The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents d(-1 Diggers

Diggers Thief of Time tds-26

Thief of Time tds-26 Science of Discworld III

Science of Discworld III Dragons at Crumbling Castle

Dragons at Crumbling Castle Nation

Nation Darwin's Watch

Darwin's Watch Interesting Times d-17

Interesting Times d-17 The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers

The Bromeliad 2 - Diggers The Science of Discworld II

The Science of Discworld II